When the world’s most famous cyclist was a Black man and a Hoosier

- By Jack Sells, TheStatehouseFile.com

-

-

At one point, Indiana had a claim on the fastest cyclist in the world. In consecutive years, Marshall Taylor won a world title and U.S. title in bicycle racing.

The sport at the time was immensely popular—“races attracted more fans than baseball, boxing, and horse racing combined,†according to Marlene Targ Brill’s book, “Marshall ‘Major’ Taylorâ€â€”and Taylor was the star.

There’s nothing probable about becoming the best in the world at something. To reach the heights he reached, Taylor needed a combination of skill, determination and luck.

And that alone would make a recount of Taylor’s life worthy of writing. But Taylor’s story is about more than a man born in Indianapolis becoming a world champion. It’s about a Black man, born 13 years after the Civil War, defying racism and sticking with his religious convictions—to the detriment of his career—on the way to immense athletic success.

Who was Major?

As Andrew Ritchie details in his biography on the cyclist, while Taylor’s grandparents had been slaves, his parents were born free. His father fought in the Civil War and later settled down with his wife and had eight children.

At a young age, Taylor became locally famous for the tricks he was able to do on a bicycle. He wore a uniform while doing so and thus earned the nickname Major. Ritchie writes that Taylor wore “a soldier’s uniform†as “a publicity gimmick designed by Hay & Willitsâ€â€”the bicycle store Taylor worked for.

But how did Taylor, in the 1890s as a Black teenager who lived on a farm, have a bicycle to develop a skill set? And how did he get a job in the state capital?

A lot of it came down to luck. His dad secured a job as a coachman for a white family, and after going with him to work sometimes, Taylor became close friends with the son, Daniel Southard. In Taylor’s words, he was “employed as his playmate and companion.†He lived with the Southards in Indianapolis and was even educated alongside Daniel.

“There, at the Southards’, besides learning to read and write from a private tutor, he learned to talk, think and relate to others in ways different from those he would have learned at home or at a simple rural school,†wrote Ritchie.

Taylor received a better education than he would have and got his start with a bicycle because of his relationship with the Southards.

His second family eventually moved, and Taylor went back to his home on the farm, but it wasn’t much later that Taylor was once again taken in by someone—professional cyclist Louis “Birdie†Munger—and moved to Massachusetts.

“He had gone from being a ‘millionaire’s son’ with the Southard family to being all but adopted by the man [Munger] who had been the world’s fastest cyclist,†Michael Kranish wrote in “The World’s Fastest Man.†“Throughout his life, this would be a pattern, as he simultaneously faced the most brutal racism but also was embraced by a series of benefactors who were impressed by his talent and treated him without regard to race.â€

Being a Black professional cyclist at the turn of the century

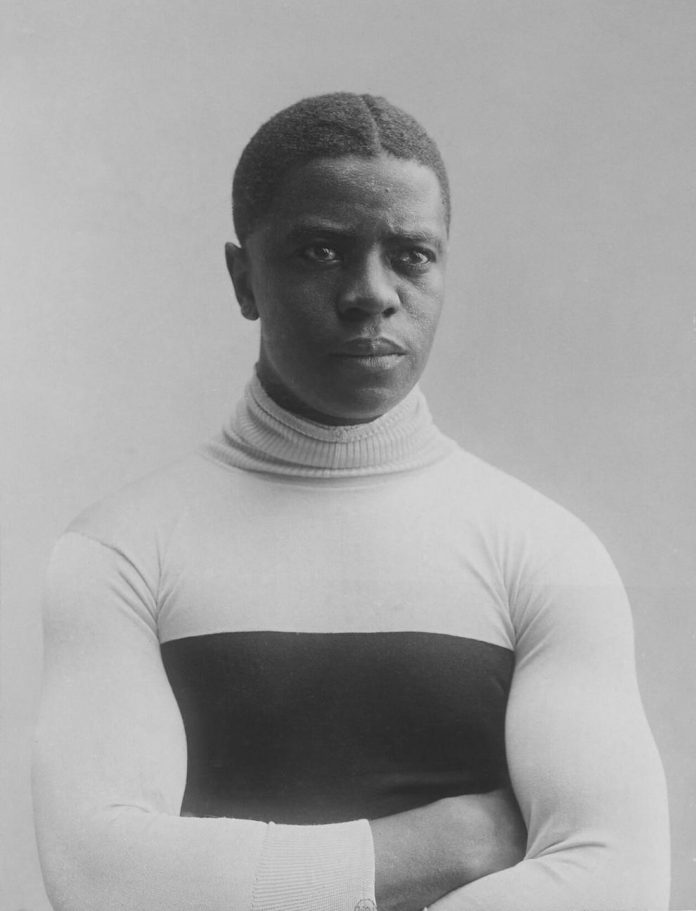

Dated from either 1906 or 1907, this was one of many photos of Taylor taken by French photographer Jules Beau (1864-1932). On Taylor’s 1901 trip to Europe, Michael Kranish wrote, “Taylor’s arrival coincided with the introduction of what would be called photojournalism.†Beau took more photos of Taylor than anyone else, according to Kranish.

This image, now in the public domain, is from the Bibliothèque national de France, France’s national library, and is a scan of the original picture. It was accessed through Wikimedia Commons: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Major_Taylor,_1906-1907.jpg  Photo by Jules Beau.

Taylor was in uncharted territory when, in 1897, he “became the first black cyclist to enter bicycle racing as a full-time professional,†according to Ritchie.

Taylor, while aided by fans and an often supportive press, still faced racism while in his sphere as a professional athlete—from competitors, race organizers and some newspapers. And this was on top of what occurred in the more private realm. There are numerous examples of Taylor being refused entry into a restaurant or hotel when traveling to compete.

Taylor also lost multiple chances to win a U.S. championship or world title. Sometimes this was because of nefarious actions from race organizers and professional cyclist leagues, and other times Taylor chose to take principled stands.

The cyclist faced a particularly infuriating and demoralizing sequence of events in Missouri in 1898.

Taylor traveled to St. Louis to race and couldn’t find a hotel that would allow him to stay there, leaving him to seek shelter with a local family. Not wanting to inconvenience them, Taylor would ride his bike to a restaurant at a train station for every meal.

Or at least he did so until he was told he could no longer eat there. (A Black waiter stood up for Taylor and was fired as a result.)

Then a race got postponed to a Sunday, but Taylor had been clear before that he wouldn’t compete on that day of the week due to his religious convictions. “Taylor had in fact been promised … that there would be no Sunday racing, and this decision in St. Louis was an obvious and immediate betrayal,†Ritchie wrote.

Taylor wanted to go home to Worcester, Massachusetts, but was convinced to travel to another race in Missouri by a race promoter who said he owned a hotel where Taylor could stay. And yet the man went back on his word, instead saying there was a Black family Taylor could stay with, and Taylor left town, breaking his contract in the process.

Prior to this—before Taylor transitioned to cycling professionally—the League of American Wheelmen voted it would no longer accept Black cyclists as members.

Strongly agreeing with the move, a columnist for The Referee, described as “a weekly cycling trade journal with a large circulation†by Ritchie, lambasted those not in favor.

The gist of the racist tirade? The inclusion of African Americans in the league was “an evil which would sooner or later have ruined the LAW in the great southland.â€

The columnist made clear he had “no desire to deprecate … the race,†but that was incongruous with almost every other sentence in the column.

“Were these enthusiastic lovers of the blacks to question those who know, they would learn that the negro has little interest in anything beyond his daily needs, his personal vanity and a cake walk or barbers’ hall now and then,†it read.

Black men were a monolith, according to the writer—illustrated by him description them in the singular. “He is a lazy, happy-go-lucky animal†with “lack-brain carelessness†and “thievish … proclivities,†he wrote.

While not directed at Taylor, this columnist’s opinions were mirrored by plenty of others when Taylor was a professional athlete.

And the onslaught of discrimination led to Taylor attempting to alter his appearance through an extreme measure—or at least, what would be seen as extreme today.

Kranish’s account includes details of how Taylor and Munger endeavored to change Taylor’s skin color through advertised products.

“Birdie Munger … tried in various ways to make me white … and on one occasion by the bleaching process,†according to Taylor. “On that occasion, my hair turned red almost by the action of the cream and the skin was nearly burned off me. Then I thought I was going to die.â€

“We told him that we would bleach him and make him white,†Munger said to the Detroit Free Press in 1897. “He took us at our word and submitted to an operation. The mixture was poisonous in the extreme.

“It was a sort of cream, and for days and days we poured it on the lad. His hair turned a sort of red, and his skin did seem to be turning whiter and whiter. But the solution was working to the detriment to the lad’s health, and we had to stop it. He has never been as dark, though, as he was before the operation.â€

African Americans during the time felt “pressured to take desperate measures they believed were needed in order to survive a Jim Crow society,†wrote Kranish. “Advertisements in African American newspapers showed before and after pictures of how a black person looked white after the treatment, which was claimed to be ‘harmless.’â€

The Journal of Pan African Studies, in 2011, published scholarship on skin bleaching in the 1920s, and said skin bleach “advertisements directed towards men were more likely to emphasize upward mobility than physical attractiveness.â€

This seems to fit with why Taylor underwent the bleaching. Munger said it came down to Taylor being “refused entry to a race owing to his color.â€

Major’s major accomplishments

Today, the typical American’s knowledge of cycling may be limited to the Tour de France, and while the multi-day, long-distance race was around during Taylor’s heyday, Taylor largely kept to short distances on a track.

Taylor set so many records ranging in distances from â…• mile to 2 miles, that it would be tiresome to list them. (But Kranish did for those interested.) Maybe most notably, in a two-day span in 1898, Taylor set world records in seven different distances.

Kranish also broke down Taylor’s first tours through Europe. In 1901, Taylor got first place 42 times—according to Taylor, 39 according to others—second place 11 times, and third three times.

And the man was similarly dominant the next year, winning 40 races, finishing second 15 times and nabbing third place twice.

The various racing organizations and ways to win championships can be difficult to follow, but in 1899, Taylor was named the world champion in the mile, and in 1900, he became the American sprint champion.

As probably expected, Taylor’s career was full of historical firsts and feats.

Ritchie lays it out: “He was one of the first black athletes to be a member of an integrated professional team, the first to have a commercial sponsor, the first to establish world records. He was the second African-American world champion in any sport, preceded only by George Dixon, the bantamweight boxer. He was the first black athlete to compete regularly in integrated competition for an annual American championship.â€

Taylor’s legacy

During his lifetime, the cyclist reached a level of popularity that meant famous people from other fields followed his career.

Kranish wrote about two separate examples of this. Before Taylor’s 1902 tour in Europe, Booker T. Washington—about a year removed from being invited to the White House by President Teddy Roosevelt—took some students to see Taylor before he got on a boat to cross the Atlantic Ocean.

And in 1916, Roosevelt himself visited Taylor.

“Taking into consideration all the millions of human beings on the face of the earth, whenever I run across an individual who stands out as peer over all others in any profession or vocation it is indeed a wonderful distinction, and honor and pleasure enough for me,†Taylor recalled the former commander-in-chief saying.

“He had become the most prominent black American athlete, and one of the most celebrated black Americans,†Ritchie said, referring to the end of the 1898 season.

Taylor reached some high highs during his life but he faced tough times towards the end of his life. At the end of his career, Taylor turned back on his promise not to race on Sundays. After retiring, he got involved in multiple business ventures that failed and put him in an unfortunate spot financially.

In 1932, Taylor died in Chicago at the age of 53, impoverished and estranged from his wife and daughter.

Because of this, and aided by the fact that cycling’s popularity waned, Taylor’s death went largely unnoticed for a long time. Then, in 1948, a group called the Bicycle Racing Stars of the Nineteenth Century gave Taylor, in Kranish’s words, “a proper memorial.â€

Since then, there have been efforts to tell Taylor’s story to the public. The Major Taylor Association is a nonprofit that raises money to preserve a statue of the cyclist in Worcester, Massachusetts, as well as “to educate people about Major Taylor’s life and legacy.â€

Forty-one years ago, the Major Taylor Velodrome in Indianapolis was built and is now home to the Major Taylor Racing League and Marian University’s 47-time national champion cycling team.

And in June, the Major Taylor International Cycling Alliance will be hosting a convention named after Taylor in Indianapolis.

Taylor’s legacy to those who know of him is likely the success he had as a Black cyclist, and as Kranish noted, Taylor wrote in his autobiography that he hoped Black kids would “carry on in spite of that dreadful monster prejudice, and with patience, courage, fortitude and perseverance, achieve success for themselves. I trust they will use that terrible prejudice as an inspiration to struggle on to the heights in their chosen vocations.â€

Taylor’s own “patience, courage, fortitude and perseverance†make up the bedrock of how he was able to become the fastest man in the world and why he can now serve as an inspiration to anyone willing to learn about him almost 150 years after he was born.

Taylor, in a letter that he sent back to a fan who had applauded him for continuing to not race on Sundays, expresses his overarching attitude toward life:

“I am laboring under the greatest temptation of my life, and I pray each day for God to give me more grace and more faith to stand up for what I know to be right. … I have no fear for the future, for I feel that I will be taken care of, although things seem very cloudy at present. … Yours in Christ, Major Taylor.â€

Footnote: Quotes from Taylor, whether from his autobiography or newspapers covering him, as well as quotes from his contemporaries, came from the three books referenced in the article: “The World’s Fastest Man” by Michael Kranish, “Major Taylor” by Andrew Ritchie, and “Marshall “Major†Taylor” by Marlene Targ Brill.