Requiem for the Say Hey Kid

In the days when he played baseball, if he had a choice, my son always picked the number 24 for his uniform.

John Krull, publisher, TheStatehouseFile.com

He did so to honor his favorite baseball player when he was growing up, centerfielder Grady Sizemore of the then Cleveland Indians. Sizemore is one of the great might-have-been of baseball history, a young player gifted with immense natural speed, power, and grace. He would have had a Hall-of-Fame career if he hadn’t played with reckless abandon, running into outfield walls in pursuit of fly balls when most other players just would have tried to play the carom.

Maybe, though, Sizemore felt he had something to live up to.

The number 24 had a pedigree.

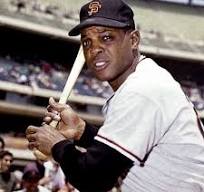

For years, it belonged to the man many knowledgeable observers still consider the greatest baseball player who ever lived, Willie Mays. Mays also played centerfield, but with an artfulness few if any other baseball players ever rivaled.

When Mays began playing baseball professionally three-quarters of a century ago, the game’s wise men marveled at his physical gifts. In the parlance of a later age, he was a five-tool player, one who could hit for both average and power, run fast, field and throw for distance with accuracy.

He was, they said, a “natural.”

But those descriptions of his supposedly innate prowess demonstrated the casual racism of the era.

Mays came into the major leagues at the same time as two other great centerfielders, Duke Snider of the Brooklyn Dodgers and Mays’ almost exact contemporary, the New York Yankees’ Mickey Mantle.

When sports reporters would gush in Mays’ presence about his inherent physical gifts, he would deflect the praise by pointing out that Mantle could run faster than he could.

Mantle, for that matter, also was a switch hitter who could drive a baseball for greater distances than anyone else playing the game at that time.

At the time, sportswriters wrote off Mays’ deflections as modesty.

There likely was more to it than that. Mays also may have been trying to tell them that he was among the greatest players who ever lived—and maybe was the greatest—not just because he’d won the genetic lottery.

He was that good because he worked at his game with rigor and intelligence few other human beings could match.

That’s why he prevailed over his rivals, including the prodigiously gifted Mantle.

Even though Mantle ended up in the Hall of Fame—just like Mays—he did not have the career Mays did. By the time the two men had hung up their cleats, Mays had hit 124 more home runs than the Yankee centerfielder, and his lifetime batting average was several points higher than Mantle’s. Mays also captured a dozen Golden Glove honors for his skill as a defensive player.

Some of Mays’ success can be attributed to his discipline. In an era in which many players—including Mantle—were lax about conditioning, Mays took care of his body. This allowed him to continue playing at an elite level until he was almost 40—and to remain in the major leagues until he was 42.

But his fierce intelligence was what accounted for many of Mays’ incredible achievements.

He liked to find a way to get to second base early in a game. If he did, he would decipher the signals the catcher used to call the game. From there on out, Mays could alert any teammate who was at bat what pitch was coming.

In other words, Willie Mays was so good at baseball because he was one of the smartest players ever to step on to a diamond.

My son was born too late to see Mays play. I only saw him on television.

My late father, though, saw Mays in person often, the first time when the superstar in the making was playing minor league ball in the Twin Cities, where Dad grew up.

Mays, Dad said, was like no other player he’d ever seen. He was a ballplayer who always knew not just where he needed to be and what to do, but also where everyone else on the field was and what they were doing.

Mays was so good that many other gifted players, including my son’s hero, spent decades crashing into walls trying to chase his ghost.

Willie Mays died the other day. He was 93.

May he rest in peace.

John Krull is director of Franklin College’s Pulliam School of Journalism and publisher of TheStatehouseFile.com, a news website powered by Franklin College journalism students. The views expressed are those of the author only and should not be attributed to Franklin College.