Leaders of an Indiana group aimed at supporting independent political candidates say the state’s time in the national congressional redistricting spotlight gives them hope that the Legislature will advance election reforms.

On top of Independent Indiana’s list is eliminating straight-ticket voting in which those casting election ballots can vote for all of a party’s candidate with a single push of a button.

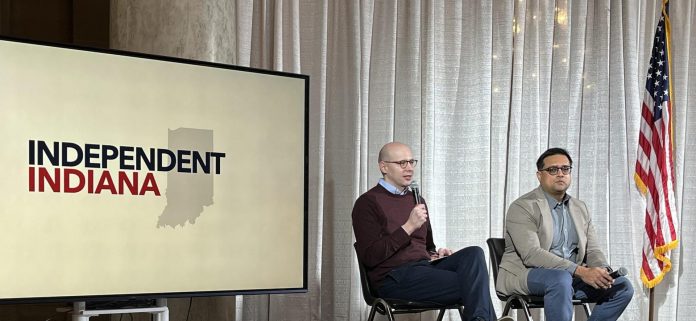

Independent Indiana organizers, who launched the group this fall, released Monday a report on the competitiveness of the state’s elections. They said straight-ticket voting is among the greatest obstacles independent candidates face since voters don’t even see the names of those candidates.

A poll conducted for the study found that 62% of voters considered straight-ticket voting a “bad thing,” with 26% in support. The highest level of support was from among Republicans, but they were 36% in favor and 49% against the practice.

Nathan Gotsch, executive director of Independent Indiana, said the secretary of state’s office does not track how many straight-ticket votes are cast statewide.

“But we went through and looked at the top five largest counties in the state and over 50% of voters in the last election in those counties voted straight ticket,” Gotsch said.

Call to eliminate straight-ticket voting

Bills to eliminate straight-ticket voting have been introduced numerous times in the Legislature over the past decade without winning passage.

Such issues have been dismissed in the past as ones of little interest to the public. But that was also the view about a topic like congressional redistricting before the monthslong debate ended with its defeat by the state Senate last week, said Jay Chaudhary, a board member of the nonprofit Center for Independent and Effective Government, which is Independent Indiana’s parent organization.

“Nobody cares about redistricting, right? But we saw the absolute fire storm and really the power of the people in beating that back,” said Chaudhary, who was director of the state’s Division of Mental Health and Addiction under Republican Gov. Eric Holcomb.

Indiana is one of only six states that currently allows straight-ticket voting, according to the group.

Gotsch said a new factor in the straight-ticket voting discussion will be the impact of school board candidates being allowed to list their political party affiliation starting with the 2026 elections. The partisan school board bill adopted earlier this year, however, does not allow straight-ticket votes to count in those races.

“I actually think in a lot of Republican areas, you could find Republican school board members losing because of that under vote,” Gotsch said. “So many people are going in, voting straight ticket and then those Republican school board members are not benefiting from those votes.”

The group is also advocating for a lowering of the signature threshold independent candidates must meet in order to qualify for the election ballot.

Those candidates must now collect petition signatures from registered voters equal to 2% of the most recent secretary of state vote in their district. For a statewide race, that means nearly 37,000 signatures.

Gotsch, who was an independent candidate in 2022 for northeastern Indiana’s 3rd congressional district seat, said that the 2% requirement was enacted in 1980 and creates a barrier for those wanting to run as independents.

Poll finds many voters dissatisfied

Independent Indiana’s report also blames gerrymandering for what it said resulted “in a small, unrepresentative slice of voters effectively determining who ultimately holds most elected offices.”

The report cited the 2024 primaries, in which 17% of Indiana registered voters cast ballots — an estimated 13% in the Republican primary and 4% in the Democratic primary.

The report’s poll found that 53% of overall Indiana voters were dissatisfied with their election choices, with 40% satisfied. Republican voters, however, were satisfied with their choices by a 68%-26% margin.

For political party identification, the poll found:

- 29% of voters considering themselves Republicans

- 15% saying they were independents who leaned Republican

- 21% said they were Democrats

- 11% independents who leaned Democratic

- 15% independents

- 8% declined to answer

Regarding the state’s major parties:

- 33% had favorable opinion of the Indiana Republican Party, with 45% unfavorable

- 25% had favorable opinion of the Indiana Democratic Party, with 43% unfavorable

The poll, conducted by North Star Opinion Research, was taken of 604 registered voters in early October with a margin of error of 3.99%. North Star regularly polls for GOP candidates and national Republican committees.