|

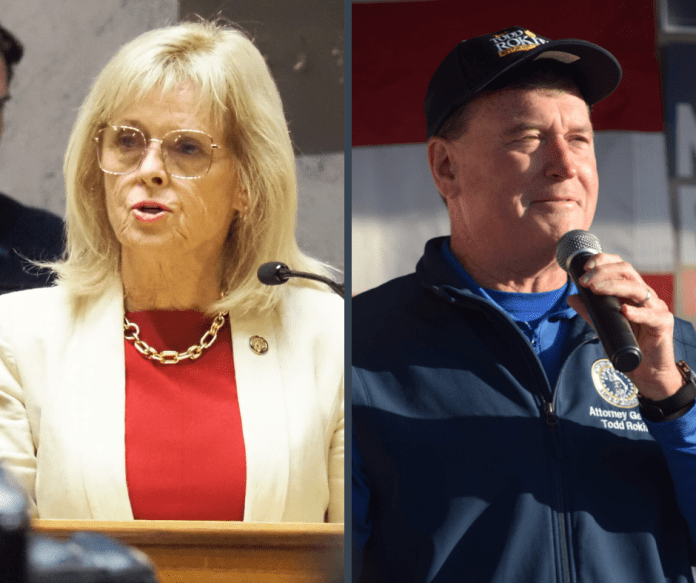

New HHS rules echo Hoosier common sense U.S. Health and Human Services (HHS) Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr. on Thursday announced bold federal actions to protect children from chemical and surgical mutilation done in the name of “gender transition.” Attorney General Todd Rokita was one of two state attorneys general attending the announcement in the nation’s capital. |

|

|

| These actions, among others, came a day after the U.S. House of Representatives passed the Protect Children’s Innocence Act, which would criminalize the act of performing sex-rejecting on minors.

In Indiana, Attorney General Rokita has prioritized protecting children from these cruel and dangerous procedures. In federal court, Attorney General Rokita has strenuously and successfully defended an Indiana law enacted in 2023 that prohibits medical practitioners from providing gender transition procedures to minors, including surgeries, hormone treatments and puberty blockers. In 2024, Attorney General Rokita co-led a successful 22-state amicus brief to the U.S. Supreme Court supporting the State of Tennessee’s authority to enforce a law that — similar to Indiana’s — prohibits medical interventions before age 18 intended to alter boys’ or girls’ appearance and physiology so that they resemble members of the opposite sex. Also in 2024, Attorney General Rokita and 14 other states successfully sued the Biden administration over a rule transforming a federal prohibition on sex discrimination into one on gender identity discrimination. The rule could have forced medical providers to perform surgeries and administer hormones to both children and adults for the purpose of gender transition. |