Nonprofit Hospital CEO Compensation: How Much Is Enough?

The COVID-19 pandemic exposed vast disparities in health care not only in access to care and patient outcomes but also in the inequities of hospitals’ pay for different employees. While some hospital executives took modest pay cuts for a few months to make up for financial losses, more than 80 percent of hospitals continued to provide CEO bonuses, even as other hospital workers were furloughed or had their pay slashed. As is often the case, one story can tell a much larger and more important story. Last year, a hospital technician whose take-home pay was $30,000 per year contracted COVID-19 on the job. Upon his return to work, he was named employee of the month and given a $6 gift voucher for the hospital cafeteria. The hospital system CEO—who was not on the frontlines of COVID-19—received a 13 percent boost in his total compensation, which was worth $30.4 million.

While such glaring chasms in pay are not unique to hospitals, the pandemic has triggered the question of whether executive compensation should be part of the broader discussion about equity within our health care system, especially as minorities and women are often the employees at the lower end of the wage spectrum. Moreover, the impact of hospital employee wages goes beyond the individual. Since hospitals are often the largest single employer in their region, the salaries they pay their workers may have a significant impact on the financial stability and income security of the entire community.

This story and the embedded facts raise two key questions: How big is the gap between the pay of the workforce and the CEO, and what are the implications? We explore these questions using new data and insights from a recent study conducted by the Lown Institute.

In the world of nonprofit pay scales for executives, hospitals are outliers. A 2021 report from the Economic Research Institute (ERI) found that the average annual CEO pay in most nonprofit industries was between $100,000 and $200,000 in 2018. The two exceptions were university CEOs, who were paid an average of $350,000, and hospital CEOs, who were paid on average $600,000. But the average belies the true dimensions of executive salaries in health care systems. In 2018, Bernard Tyson, then-CEO of nonprofit health care giant Kaiser Permanente, made nearly $18 million, making him the highest-paid nonprofit CEO in the nation. The previous year, the top 10 highest paid nonprofit health system executives each made $7 million or more. Even the bottom 25 percent of nonprofit hospital CEOs enjoyed annual compensation of about $185,000 according to ERI—more than the highest-paid quartile for CEOs in nonprofit arts and culture, environmental, human services, and religion-related organizations.

These differences hold even when comparing nonprofits with similar revenues in health care and in other areas. The highest-paid executive of the American Red Cross, a national nonprofit with 600 chapters and revenue of $3.6 billion, received about $800,000 in total compensation in 2018. In comparison, the president and CEO of the Ochsner Clinic Foundation, a large academic health system hospital in New Orleans with revenue of $3.4 billion, made $5 million in compensation the same year—about the same amount as the 10 highest-paid executives from the American Red Cross combined.

Pay Equity At Nonprofit Hospitals

The wide divergence between nonprofit hospital CEO compensation and other nonprofit entities prompted us to examine hospital pay equity as part of the Lown Institute Hospitals Index, a big-data project launched in 2020. For the hospital pay equity metric, we compared the difference between top executive compensation and the average wage of hospital staff without advanced degrees. We included lower-wage staff, such as janitorial and kitchen staff, and medical-records personnel, and excluded professional staff such as physicians and nurse practitioners, whose jobs require specialized degrees. We used information from Internal Revenue Service (IRS) 990 forms, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, and the Bureau of Labor Statistics for the year 2018 (the latest available data).

In calculating the index, we imputed missing values; we also allocated system CEO salaries to individual hospitals pro-rata by revenue share. For the analysis we report below, however, we focused on the subset of 1,097 nonprofit hospitals on the Lown Index, for which pay equity was calculated without any imputation or prorating. Only hospitals that had executive compensation data available for the facility in IRS 990 forms are included in this subset. We used a 40-hour workweek to translate annual salary and bonus figures into hourly wages.

Within this set of more than 1,000 nonprofit hospitals, we found that hospital executives on average made eight times the wages of workers without advanced degrees in 2018.

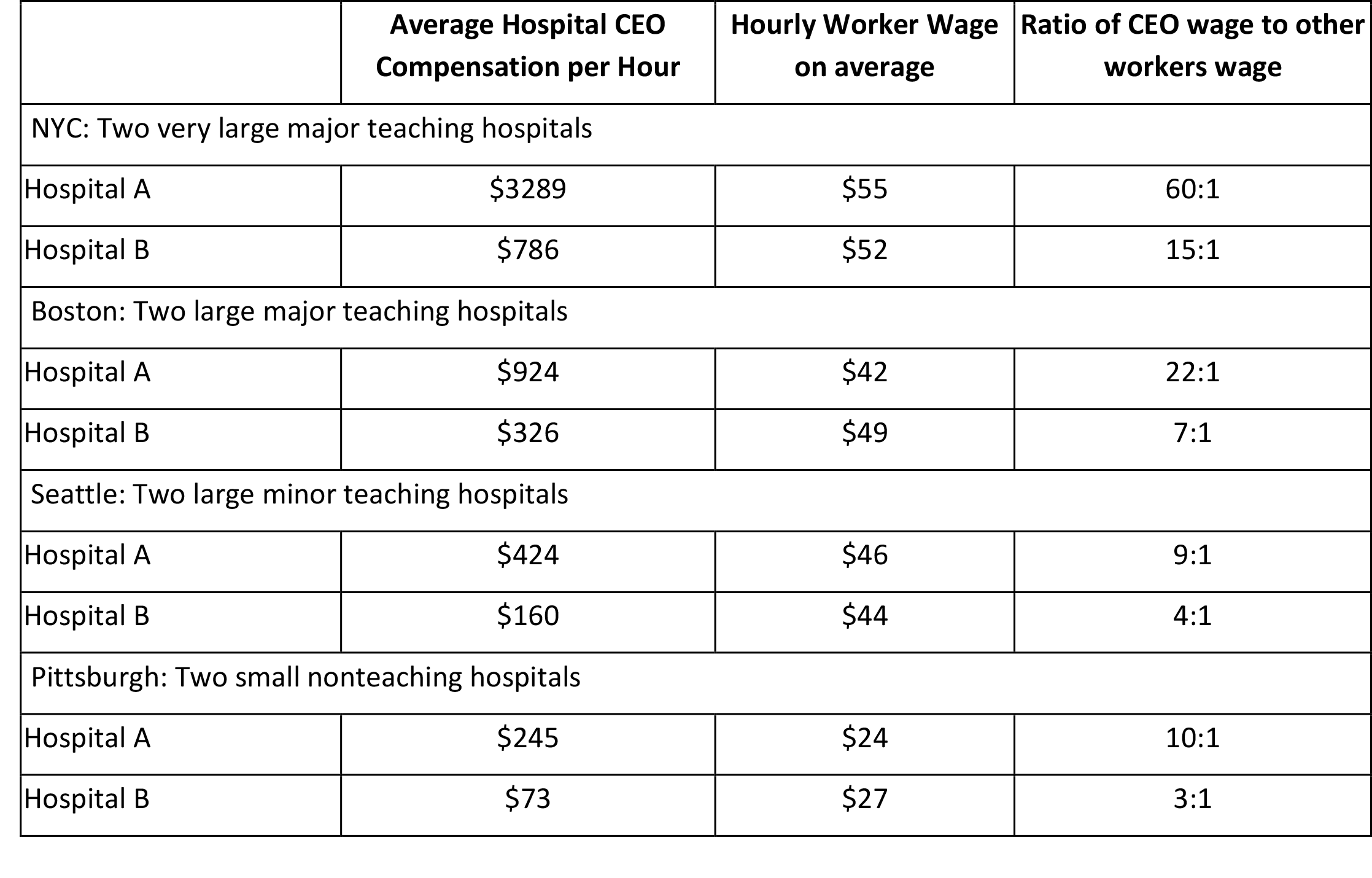

However, this ratio varied widely. Some hospital CEOs were paid at twice the rate of other workers, while the highest-paid received 60 times the hourly pay of general workers (see exhibit 1).

Exhibit 1: Pay equity, top 50 and bottom 50 hospitals

Source: Authors’ calculations based on Lown Institute Hospitals Index.

Source: Authors’ calculations based on Lown Institute Hospitals Index.

Determinants Of Hospital CEO Compensation

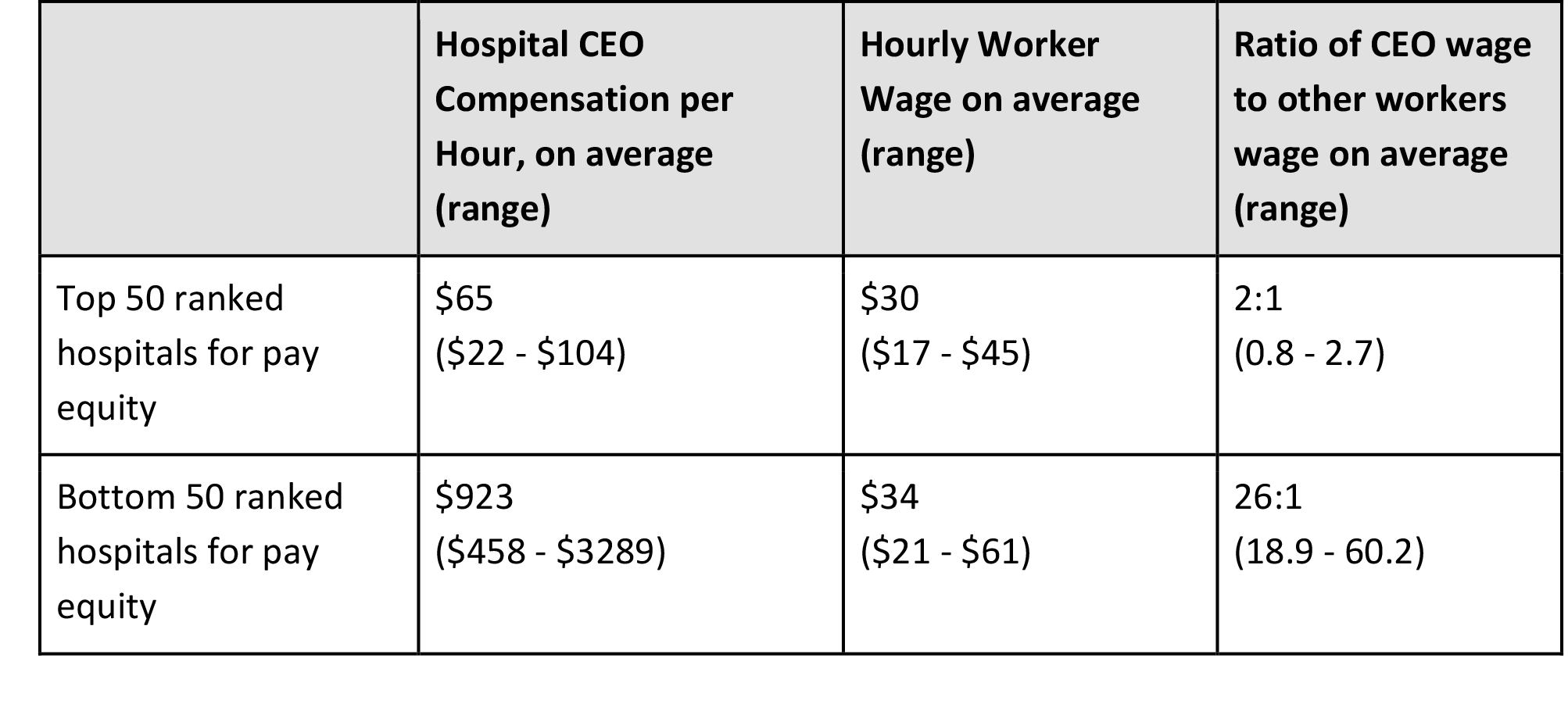

Hospital CEOs are compensated primarily for the volume of patients that pass through their doors—so-called “heads in beds.†Previous research on hospital executive compensation finds that higher compensation is strongly associated with the number of beds, at a rate of an additional $550 in salary per bed. Another study of 35 CEOs at Connecticut nonprofit hospitals found that from 1998 to 2006 they were incentivized to increase the volume of privately insured patients at the expense of those with public or no insurance. This is part of the underlying business model that drives the nonprofit hospital landscape: Volume matters, and high-margin volume matters the most for the bottom line. We see the relationship between hospital size and executive compensation in exhibit 2 below. Although both CEO compensation and worker wage increase in a stepwise fashion as hospital size increases, the increase in CEO compensation tends to exceed that of worker pay for larger hospitals, giving them a higher pay equity ratio.

Exhibit 2: Pay equity in nonprofit hospitals by hospital size

Source: Authors’ calculations based on Lown Institute Hospitals Index.

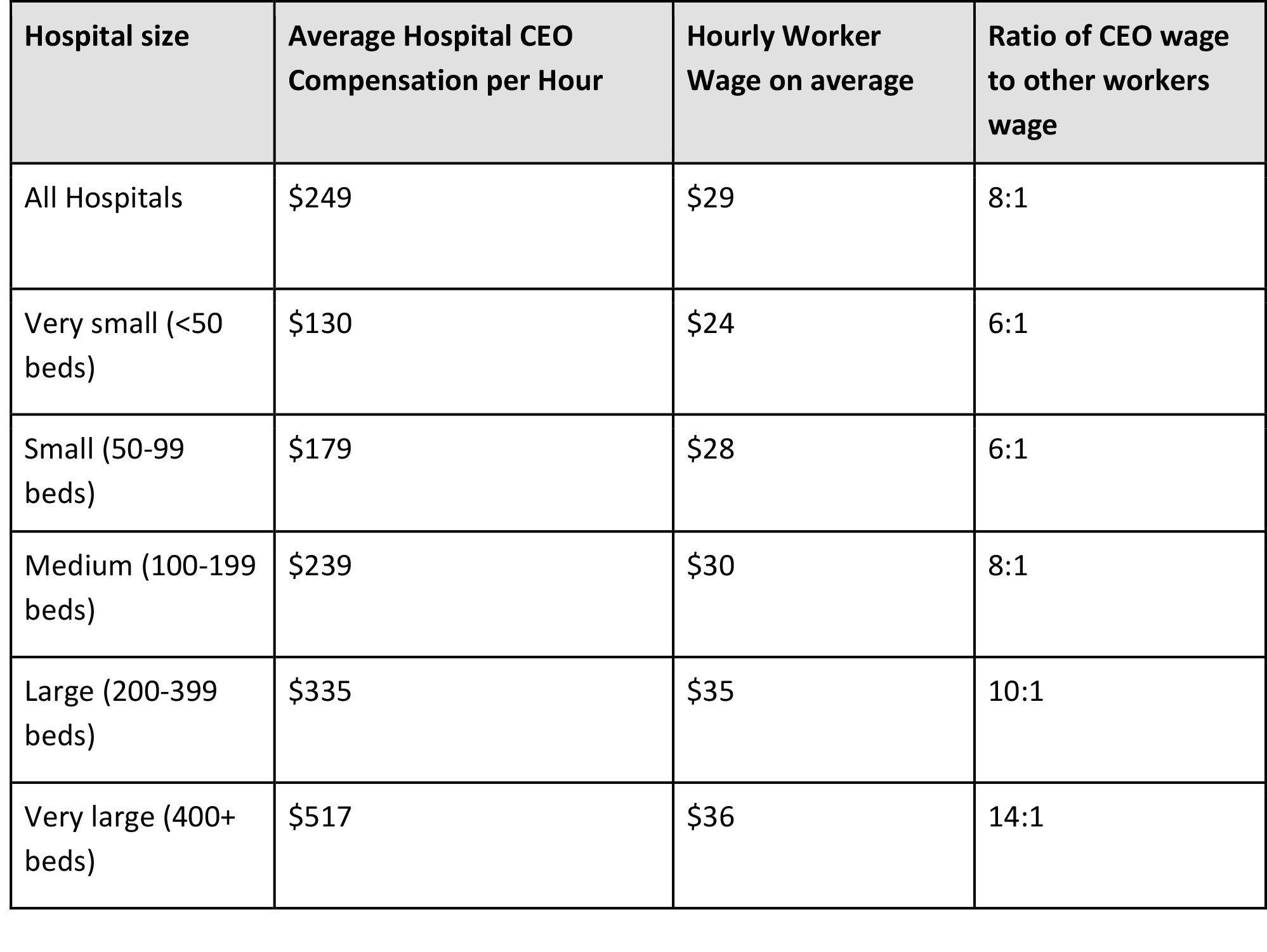

Size is not the only characteristic that matters for pay equity. Among larger hospitals with 400 or more beds, there was still significant variation in hourly executive compensation, ranging from $88 to $3,289 per hour. According to the Lown Index data, urban location and teaching status are also associated with higher executive hourly compensation compared to general worker wages, which supports findings from previous research as well (see exhibit 3).

Exhibit 3: Pay Equity By Hospital Type

Source: Authors’ calculations based on Lown Institute Hospitals Index.

Source: Authors’ calculations based on Lown Institute Hospitals Index.

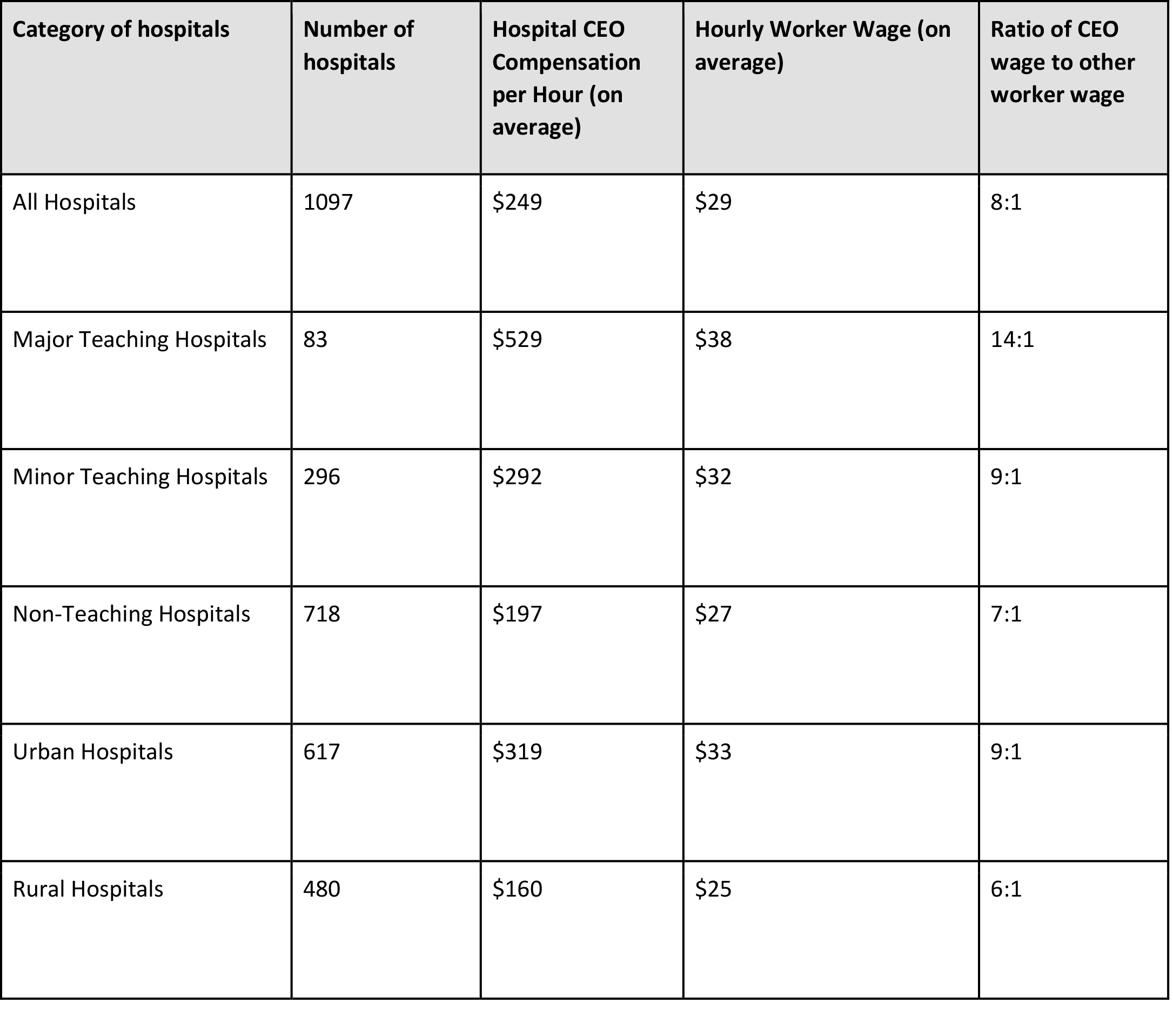

Yet, there are continued discrepancies in compensation unexplained by location, hospital size, and hospital type. We found variation in executive compensation among large teaching hospitals and small nonteaching hospitals alike, even those located in the same cities (see exhibit 4 for examples). In some cities, similar hospitals pay their CEOs two-four times the hourly rate other hospitals do, despite paying their workers without advanced degrees similar or lower rates.

Exhibit 4: Comparisons of hospitals of similar size and type in selected cities

Source: Authors’ calculations based on Lown Institute Hospitals Index.

Hospitals in certain Mid-Atlantic/New England states had especially high rates of executive compensation compared to average worker wage. In Connecticut and Maryland, CEOs made 13 times the average hourly worker’s wage, while in Delaware, New York, and New Jersey, CEOs made 12, 11, and 10 times average hourly wages, respectively. By comparison, hospitals in some Midwestern and Great Plains states had much lower rates. In Idaho, Mississippi, and North Dakota, CEOs made about five times the average hourly worker’s wage. Hospitals in Nebraska, South Dakota, Wyoming, Kentucky, Washington State, and Arkansas also had average ratios below six.

The History Of Hospital CEO Compensation

Although COVID-19 brought hospital finances and pay scales to greater public awareness, the rise of nonprofit hospital CEO pay has been decades in the making. Hospital revenue began to climb in the 1960s with the advent of Medicare and increasing insurance coverage. With increased revenue came a shift in attitude that helped transform many hospitals from community-focused nonprofits into big businesses. Hospitals began hiring more administrative staff, restructured their boards to include more leaders from the corporate sector, and even changed their mission statements to reflect the increasing importance of financial considerations.

Naturally, the new corporate members of hospital boards brought their values and experience from the for-profit world into the governance culture of the hospital. Today, hospital boards compare the compensation of their CEOs not to other community-based nonprofits but to their for-profit publicly traded hospital CEO peers, who themselves are compared to leaders in the largest industrial and financial companies trading on Wall Street. Since many boards set CEO salaries by obtaining “comparable†salary data, this becomes an ever-spiraling upward cycle.

As hospital policies and culture have become more aligned with big businesses, hospital executive compensation has swelled, mirroring the climb in CEO wages across all of corporate America that began in the late 1970s and continued despite the Great Recession that began in 2008. According to the Economic Policy Institute, the average realized compensation of US CEOs, adjusted for inflation, grew by 105.0 percent from 2009 to 2019, while typical worker compensation increased by just 7.6 percent. Similarly, from 2005 to 2015, the average compensation of major nonprofit hospital CEOs rose by 93 percent, from $1.6 million to $3.1 million, while average hospital worker wages increased by a mere 8 percent in that decade.

How Should We Pay Hospital CEOs?

Our collective experience with the COVID-19 pandemic has provided an opportunity for the public, hospital boards, policymakers, and regulators to reflect on recent trends in hospital compensation and to rethink how we should pay nonprofit hospital CEOs. Hospital boards in particular, as the final arbiters of CEO pay, should consider the following questions:

- What should be the fundamental basis for CEO pay: size and complexity of the organization; organizational revenue; patient outcomes; community health; comparisons to for-profit corporate CEO pay?

- How should complexity or the degree of difficulty of the job be measured?

- Is there a maximum acceptable level of compensation? If bonuses are offered, what should they be based on?

- Should there be a norm established regarding the most equitable multiplier between CEO pay and general employee pay? Should there be a maximum?

- Should CEO pay and total compensation be reported and transparent for all individual hospitals as well as hospital systems?

- How much CEO pay is enough to ensure that hospitals are able to recruit effective leaders without further inflating the cost of health care, which is borne by all of us, or increasing wage disparities that harm communities?

- Revenue certainly places limits on what a hospital can pay. But when revenue is large, how much more should CEOs be rewarded for enhancing it further?

Our opinion is that as institutions dedicated to the public good and the health of their local communities, nonprofit hospitals should be measured by the value they create—both business value and social value. It is clear that size alone does not equal value. In the real world, a CEO of a 1,000-bed hospital is compensated more because more dollars are flowing through the institution, not because the job is that much harder than that of a CEO of a 500-bed hospital. They are rarely if ever compensated on the basis of their stewardship of the community’s health.

As a society, we need to develop a set of factors that gives CEOs incentives to fulfill the hospital’s social mission. For example, CEOs could be rewarded for improving clinical outcomes, patient safety, and racial health disparities. They could be rewarded for being good stewards of public monies by improving cost efficiency. The complexity of the job should also be considered, not only based on the size of the hospital or system but also the hospital’s patient mix and a financial cushion. Currently, hospitals with a wealthier and well-insured patient mix tend to pay their executives the most, although arguably hospitals that care for more publicly insured or uninsured patients and have chronically thin margins require more skill to manage successfully.

It’s time for a public discussion of these issues. In creating our pay equity metric, we sought to create a platform for this much-needed conversation. We hope it is the start of a long process that will engage all stakeholders in discussing the importance of aligning incentives to create real value in US health care.

Editor’s Note:  The issues addressed in this article were explored further at a February 15 event featuring two authors of this Forefront article (Saini and Brownlee) as well as Health Affairs Editor-in-Chief Alan Weil and Merrill Goozner.

Posted by the City-County Observer without bias or editing.