GAVEL GAMUT

By Jim Redwine

www.jamesmredwine.com

(Week of 11 November 2024)

THE SWEET SCIENCE REVISITED

For those few of you who might miss reading my weekly column, Gavel Gamut, I will

point out to you that this past week I fractured my shoulder while working around JPeg Osage

Ranch. I feel I must rely on past columns for a while, such as, those that have dealt with my

interest in amateur boxing. The following column appeared the week of September 4, 2006 and

involved Peg’s and my friend Ray Stallings from Burnt Prairie, Illinois. I will rerun it as it

appeared almost 20 years ago. I hope you enjoy reading, or perhaps rereading it.

“Amateur boxing has fewer fatalities and far fewer serious injuries per participant than

high school baseball or football. It is a sport like wrestling where the participants are matched

according to size and where bouts are won based on the number of legal blows landed on the

front, top-half of the participants. The force of the blows is not a factor. For example, a punch

that knocks a boxer down counts no more than a punch that simply lands in the scoring area.

Boxing is called the sweet science because a student of the game who can apply the

lessons of boxing when actually in the ring can defeat a superior athlete who relies on brawn. As

the old adage goes, “The race is not always to the swift nor the battle to the strong.” Of course,

the related adage is also true: “But that’s the way to bet.”

In other words, the science of boxing is only a factor in the equation. Such elements as

experience and physical abilities are often more determinative than theory. And whereas it is

often true that it is not the size of the boxer in the fight but the size of the fight in the boxer that

matters, it is also true that heart alone may not be enough.

Such was the case with our young protagonist, Ray Stallings, from Burnt Prairie, Illinois,

in his match against Calvin Brock in 1996. Should you have read this column last week, you

may recall that we left Ray all alone in the ring with one of the best amateur heavyweight boxers

in America.

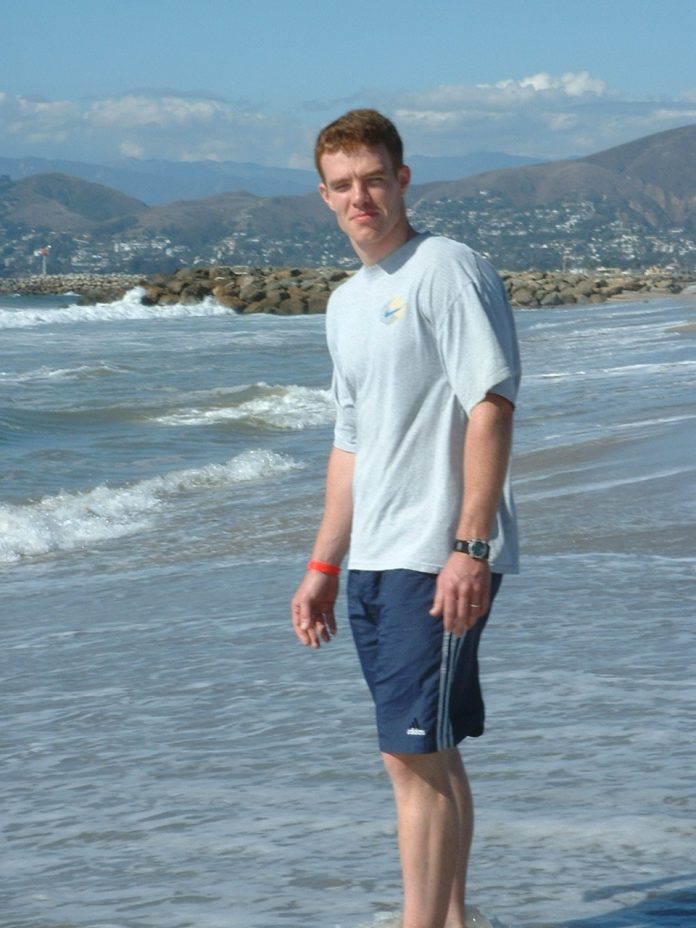

In round one, the left-handed Brock came out confident that the gawky, red headed Ray

was just there to validate Brock’s status as champion. From my position in Ray’s corner I

thought Brock was almost indolent as he kept Ray off balance with his powerful right jab, then

occasionally came back with a straight left to Ray’s head. This display went on for about the

first two minutes of the round until Ray’s nose was bloodied and his back was bleeding from

being forced into the ropes.

But with about a minute to go, Ray, who is also left-handed, came up from his position

doubled over in a corner with an awkward looping left hand that caught Brock square on the

chin. Even with the protective headgear, I could see Brock’s eyes roll up for a brief second as

his knees slightly buckled. From that point on, Ray’s character and Brock’s experience were at

war.

When Ray returned to our corner after the first round, Peg, who was working the corner

for the first time, could not bear to look at Ray’s bloody nose or his back and arms that matched

his red hair. She handed me the spit bucket and water bottle with her eyes locked on the canvas

of the ring. Peg later told me she was wondering what we were going to tell his parents, who

were also our good friends, if Ray got seriously hurt.

Ray was gasping for breath and pleading for me to pour water on his head. It took the

first half of the one-minute break just to stop the bleeding. When Ray could finally talk, he said,

“Jim, he is really good.” I almost said the truth that was on my tongue, “You’re darn right he’s

really good!” Instead I said, “You got his attention with that straight left. From now on just

keep throwing it as much as you can.”

Round two was a coming of age for Ray and an awakening for Brock. I could see the

puzzlement in Brock’s eyes and the hesitancy in his punches. I could almost hear him thinking,

“Who is this kid?” Ray pounded his straight left for the whole three minutes and the spectators

who had gathered to watch Brock’s coronation begin to yell for Ray.

When Ray struggled back to our corner after round two, I sneaked a peak at Brock’s

corner and saw his trainer giving him a tongue-lashing. Peg and I could only pour more water on

Ray as I told him to double up on his right jab and keep throwing that overhand left. Ray could

barely breathe and he could not talk. As the bell for round three rang, it was anybody’s guess as

to who would win.

Brock came out firing and Ray was too tired to block the blows. At first it looked like

Brock’s superior skills were just too much for the skinny red head from Burnt Prairie. But about

halfway through the final round, Ray figured out how to move to his left, which was away from

the left-handed Brock’s power. Then Ray figured out how to throw his left straight into the taller

Brock’s solar plexus. Brock began to wilt and Ray’s new found fans began to chant: “Red, red,

red.”

When the final bell sounded, Ray had nothing left, but that was more than Brock who had

to be helped to his corner by his worried trainer who caught my eye and put his thumbs up:

“Great fight!”

Well, you remember that amateur boxing is scored by the number of proper blows, not

the stuff that dreams are made of, and the judges gave the razor thin decision to Brock. But the

seeds of Ray’s current quest to be an Olympic champion were sown that night in 1996.

Next week if you are available, I’ll bring you up to date on where that odyssey stands.

For as you may recall, Ray had that little inconvenience of thyroid cancer to deal with between

1996 and October, 2006. That is when he climbs back into the ring in Oxnard, California, once

again against the best amateur heavyweights in America to win the right to compete for the

honor of representing his country in the Olympics.

After Ray got sick, but before he knew why he tired so easily after the first round, he kept

trying to box but kept losing. Many of Ray’s friends and some of his family were more afraid he

would get hurt than get to the Olympics. But as Rudyard Kipling wrote in his poem, “If”: “If

you can trust yourself when all men doubt you…you’ll be a man, my son!” Ray did, and Ray

is.”

For more Gavel Gamut articles go to www.jamesmredwine.com