Indiana Lt. Gov. Micah Beckwith sidestepped questions over how the $3 million increase in spending for faith-based initiatives in his office could specifically address mental health concerns in an interview with The Indiana Citizen, brushing aside questions over whether he was potentially referring to conversion therapy when he testified before state lawmakers that some of it could be spent on mental health programming.

“I kind of look at all therapy as conversion therapy,” the Republican said last week when asked if he would be open to utilizing conversion therapy, which attempts to change the sexual orientation or gender identity of LGBTQ+ people, or similar approaches. He said that conversion therapy is “a weird term” for him because he views all therapy as conversion.

Beckwith surprised lawmakers crafting the state’s biennial budget last month when he testified he wants to double spending for faith-based initiatives in his office. The request comes as the Senate is in the midst of reviewing the House’s version of the state budget.

Beckwith said during the Senate hearing that the programming will address different issues such as mental health as well as homelessness and crime, suggesting that his office can be a bridge connecting the government to nonprofits and faith-based organizations that he said are better suited to address mental health matters. When asked about partnerships with other mental health organizations, Beckwith told committee members that those plans are “up in the air” because his office is waiting to see what happens with the budget. He added that his office wants to work with nonprofits and various faith-based communities.

Beckwith during the hearing said the money would go toward roundtables in every county, connecting people to their local government officials and the salary of Tyson Priest, who Beckwith tapped as the faith-based initiatives director. He also mentioned using some of it as seed money for organizations, such as the Ten Point Coalition, that need help addressing core issues in their communities.

Beckwith did not respond to a request for a document or details regarding the spending request. Jim Kehoe, Beckwith’s communications director, said he forwarded the request to the person in the lieutenant governor’s office who handles document requests.

On social media, the pastor-turned state official has repeatedly tied matters of gender identity to mental illness. Several decades of research indicates that there is no inherent association between mental disorders and identifying with different gender identities or sexual orientations, and all mainstream medical organizations in the U.S. have concluded that diverse orientations can be part of the human experience, according to the American Psychiatric Association (APA).

In February, Beckwith posted on the social platform Instagram a screenshot of a post originally on X from Meg Brock, a contributor to the conservative news outlet The Daily Caller, where she wrote, “My name is Meg and I am a woman” and continued with a list of labels that she does not identify with.

Beckwith captioned his repost on Instagram: “Mental Illness should be treated and not celebrated.”

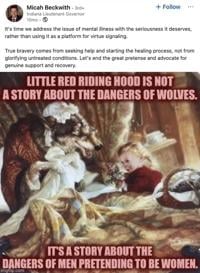

In a separate post on the platform LinkedIn from nearly a year ago, Beckwith posted a graphic linking a children’s story to matters of gender identity.

“It’s time we address the issue of mental illness with the seriousness it deserves, rather than using it as a platform for virtue signaling,” he captioned the photo. “True bravery comes from seeking help and starting the healing process, not from glorifying untreated conditions. Let’s end the great pretense and advocate for genuine support and recovery.”

Across the country, 23 states and Washington, D.C., have banned the practice, according to the LGBTQ think tank Movement Advancement Project, but Indiana specifically safeguards the practice as the only state where state law prohibits local governments from banning conversion therapy. And as part of the national backlash against transgender individuals, a number of states have pushed to reintroduce the practice.

Conversion therapy, which is practiced by both licensed professionals who claim to be providing health care as well as spiritual advisers in the context of religious practice, has resulted in increased suicides and increased thoughts of suicide, according to a 2020 report from The Williams Institute, a think tank at the University of California, Los Angeles, dedicated to sexual orientation and gender identity law.

The APA decried conversion therapy in a statement last year, saying, “Leading professional health care bodies have concluded that conversion therapies lack efficacy and may carry significant risks of harm.”

Beckwith, a longtime Noblesville pastor, said during the interview with The Indiana Citizen that he sees all mental health treatment as some version of conversion.

“What’s the difference between an AA program—an Alcoholics Anonymous program—because you’re converting an alcoholic into being sober, right?” Beckwith said. “So, every aspect of therapy is saying, ‘I need to make a conversion.’”

Meanwhile, musings of conversion therapy have made their way to some state legislatures.

In Kentucky, lawmakers last week overturned Democratic Gov. Andy Beshear’s veto of a bill that could allow conversion therapy.

Earlier this year, lawmakers in North Dakota considered a bill that would allow social workers to legally offer conversion therapy, though it failed to pass out of the Senate. A similar piece of legislation made its way into North Dakota’s legislature in 2023.

In recent years, The Texas Tribune has reported that lawmakers have tried to enact legislation that would prohibit conversion therapy—which has previously garnered support from the Texas GOP, CNN’s decade-old reporting showed—and discrimination against LGBTQ+ individuals in the Lone Star State.

During last week’s interview, when Beckwith was told that conversion therapy typically targets the LGBTQ+ population, he downplayed the debunked treatment.

“I don’t know why conversion therapy would be targeted at one group of people over another, because I just look at therapy, in general, as conversion in a good way,” he said.

The way mental health is framed could be an indicator of what treatments are implemented, suggested Andrew Flores, an expert on LGBTQ populations at UCLA’s Williams Institute and an assistant professor of government at American University.

For example, thinking primarily about gender identity, gender dysphoria—the distress that people feel when there’s a difference between their sex assigned at birth and their gender identity—or sexual orientation in the context of mental health, Flores said, could lead to certain outcomes depending on the viewpoint a person offering treatment holds.

“So thinking that maybe the best way to address mental health care is by using faith-based initiatives might open the door for care or treatment from a particular point of view that may not necessarily be, say, affirming of LGBT people,” Flores said during an interview last week.

“There’s always going to be this challenge about how these issues will get framed and discussed for the public and to kind of help mold public opinion to get to be more OK with one’s position,” Flores said.

When Beckwith was asked during the interview if the mental health initiatives would help individuals experiencing gender dysphoria, he dodged a direct answer and acknowledged that it’s a mental health concern, saying, “It doesn’t mean that we love people who are struggling with that any less.”

In response to his thoughts regarding gender identity and sexual orientation in the context of his social media posts and the faith-based initiatives, Beckwith said, “I’ll love somebody who identifies as whatever they want to identify as, I’ll love them in the same way that I love anybody else, like I’ll give them the shirt off my back. I’ll help them.

“But I also think there’s a push from that community to say, ‘You better accept us as normal.’ And that’s not what we’re going for,” he added.

When pressed further, Beckwith said that the initiatives would help people only with what they say they’re struggling with.

“Do they need help with counseling? Or do they need help with homelessness? I guess the question is: What are they looking for, right? Like, if somebody doesn’t want help, you’re not gonna be able to help that person.”

Beckwith went on to suggest that Indiana shouldn’t “play pretend games” when it comes to addressing matters related to gender identity.

“That’s what we’re being pushed to do. It’s like, ‘Hey, you better believe the way we believe,’ or else you’re a bigot, a transphobe, a homophobe, or whatever other type of -phobe they want to call us. It’s like, no, we love you guys, we care about you, but we care about you enough to say, ‘Hey, this is the way. This is the truth,’” Beckwith said.

He added: “I posted about that very openly. Say: ‘Hey, I’m not going to get pushed into a corner. I’m not going to be bullied by somebody to play along with somebody’s idea of reality.”’

This article was published by TheStatehouseFile.com through a partnership with The Indiana Citizen, a nonpartisan, nonprofit platform dedicated to increasing the number of informed, engaged Hoosier citizens.

Juliann Ventura is a political reporter who grew up in Indianapolis. Prior to joining The Citizen, Juliann reported in Washington, D.C., most recently on The Hill’s breaking news team. She earned her master’s in journalism from Northwestern University’s Medill School of Journalism and her bachelor’s in international studies and criminology from Butler University. Juliann’s reporting has been featured in The Washington Post, ProPublica, and numerous state and local publications.