Missing in action for 80 years, a World War II sailor finally comes home

- By Arianna Hunt, TheStatehouseFile.com

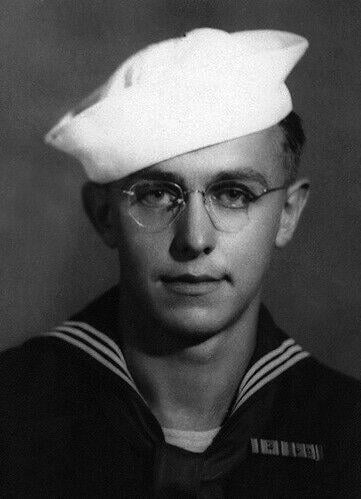

Coxswain Harley Alexander, 22, of New Madison, Ohio, served aboard the USS Glennon in World War II, taking part in Operation Neptune, the Naval component of Operation Overlord, commonly known as D-Day.

He was listed as missing in action June 8, 1944, after the USS Glennon struck a mine in the English Channel so powerful it launched some servicemen 40 feet in the air. It peeled part of the stern of the 1,630-ton, 348-foot-long destroyer away at an angle, settling it at the bottom of the channel. The ship sank the next day.

Headshot of Harley Alexander. Photo provided.

For the next 80 years, Alexander was missing, but now, long since his immediate family has passed, his whereabouts are no longer a mystery. He at last rests in Greenmound Cemetery in New Madison, next to his mother’s gravestone, where his family had put a marker for him all those years ago.

“I don’t think they expected that it would ever happen. He had been declared dead by the Department of Navy in 1949… So it was just a marker,” said William “Bill” Blue, the last surviving family member at 81, who met Alexander when he was only 20 months old. Blue lives in Connersville.

“It may have been some wishful thinking, but I don’t think they had any realistic hopes or thoughts [about Harley coming back].”

Alexander is home now because of years of work by the Defense POW/MIA Accounting Agency (DPAA), a Department of Defense agency.

“The DPAA’s mission is to find, recover, identify, and return home to their families all U.S. personnel who are still missing from our past wars and conflicts, ranging from World War II to the Korean War, the Cold War, the Vietnam War, and even up to Operation Desert Storm,” said Sean Everette, media relations chief for the DPAA.

“When a service member raises their right hand and swears to protect and defend the Constitution, they’re making an oath or promise to the country, but at the same time, the country is making a promise to them, and that promise is part of the current military’s warrior ethos of never leave a fallen comrade.”

Due to the nature of war, that ethos cannot always be accomplished immediately. That’s where the DPAA steps in, to recover service members who are unaccounted for, like Alexander.

To help identify him, the DPAA needed DNA, so they first contacted Blue and his family in 2017, Blue said.

“I was very happy when they contacted me. It made me feel good to think that somebody was going to try to associate something with our family. It would mean closure for a lot of people,” Blue said. “Unfortunately, it’s going to be late in the game, but his nieces and nephews are really pretty wound up about this.”

Jennifer McCombs was one of the other relatives who sent in DNA for testing and is one of Alexander’s nieces.

“When we first heard about it, our reaction was, this is awesome for us; it’s too bad that none of our parents, who would have been his siblings, are living because it would have been so meaningful to them,” said McCombs. “But we thought it’s nice that it happens while this next generation is still here to see him come home.”

In 1957, 13 years after Alexander went missing, pieces of the USS Glennon were salvaged when a local resident found human remains. Officials determined the remains to be of two individuals, designated X-9296 and X-9297. But because there was insufficient evidence to identify the remains, they were interred as unknowns in Ardennes American Cemetery in Neupré, Belgium.

The remains stayed in Belgium until 2021 when DPAA researchers began an effort to associate them with unresolved sailors’ cases from the USS Glennon. By August 2022, unknown remains X-9296 and X-9297 were exhumed, and on March 22, 2024, Alexander was accounted for.

“As tragic as it was, and as hard for the family, it happened 80 years ago, and it was done,” McCombs said. “It was kind of a closed chapter, and that [the DPAA] came back and put in this effort to not only exhume the remains but to reach out to find relatives to get the DNA. … They tested every bone that they recovered to make sure that they were his. I’ve just been totally amazed at the lengths that they went to do this, to return him to his family.”

Since its mission started in the 1970s, the U.S. Department of Defense has accounted for 3,372 service members; 1,527 of that number has been recovered by the DPAA since 2015, said Everette.

Even when the service member died many years ago, the DPAA has a responsibility to help put an end to the generational pain endured by the families, he said.

“We still do it for the families, even for people like Coxswain Alexander who died back during World War II. We do it for the families because we owe it to those families to give them answers of what happened to their loved one,” said Everette.

“For many of these service members, they still have family who remember. Now, it may not be family who knew them directly, that were alive when they went missing or before they went missing, but for many of these families, it’s a generational grief almost, or generational loss, where there are people who are alive today who remember their parents or their grandparents or aunt and uncles talking about their service member missing from their family.”

Even though he was so young, Blue still remembers Alexander—or at least the hole he left after he died.

“[Alexander] was a well-liked kid. I’ve heard a lot of off-the-cuff remarks about him, and then none of it was bad. All of it was that he was a nice guy, good guy to be around,” Blue said. “We’d hear about him at family reunions, and it would just be people mentioning, ‘Well, wish we had Harley here,’ and that kind of thing.”

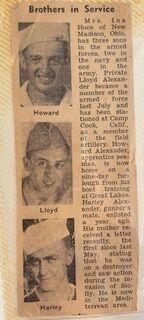

Harley Alexander holds Bill Blue in his right arm in spring 1944. Blue and Alexander had a short but meaningful relationship.

“I do have a couple of family photos and snapshots that were [of Alexander] holding me or me standing beside him. So, I would say I had a pretty good relationship with him,” Blue said.

As a veteran himself, Everette says he finds the existence of the DPAA comforting.

“So, you know, when I was in uniform, if I went, you know, if I, God forbid, went missing during combat at some point, there is an agency whose sole purpose is to find me and bring me home to my family,” said Everette.

“And so you, when we talk to present day, actively serving service members, sometimes they’ll tell us that just knowing that there’s an agency like DPAA out there that won’t forget them and won’t let them be left behind gives them a little bit of comfort and makes it maybe a smidge less scary when you have to deploy to a combat zone.”

Because McCombs still lives in the New Madison area, she was in charge of a lot of the funeral proceedings for Alexander on June 29.

“We figured [the funeral] would just be our family,” she said. “There’s a couple dozen of us, and the lady from the Navy told us, ‘Oh no, this will be much bigger. You just don’t realize’.”

Bigger it was.

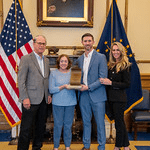

“I’m amazed at how the community has responded,” said McCombs. “We had people from American Legion, Veterans of Foreign Wars, the sheriff’s department, the Ohio State Highway Patrol, the fire department, and just local individuals. We’ve had so much response and so many people reach out. There were representatives from the governor’s office, … the local mayor’s office, there were half a dozen different representatives that awarded certificates …

“There was so much local support for it, [people] lining the streets on the route of Greenville (where the funeral home was located) to New Madison (where the cemetery was), which is about 10 miles, waving flags with their hands over their hearts. It was, it was just awesome. It was unbelievable.”

Even when the plane carrying Alexander’s remains was delayed two hours, people still lined the traffic circle and parts of the road he would pass through.

“I kind of expected that anybody who had planned to come out, to be there when we came would have given up and gone home by now. But there were a lot of people there who either waited or left and came back. Two hours behind, and they were still there,” said McCombs.

“I think everyone was just in awe that Uncle Harley was a farm boy from a small, small town—for him to get this kind of honor and recognition was … just awesome.”

After the family arrived and got situated under the blue tents at Greenmound Cemetery, as the first speaker started, it began to rain.

“It rained during the whole service, and I was surprised because people who were there who weren’t family, who just came to stand and honor him, nobody left. Nobody left. I didn’t see one person leave. That tremendous community support, that was, that was really humbling,” McCombs said.

“I had no clue that it would be as touching to so many people as it has been.”

FOOTNOTE: Arianna Hunt is a reporter for TheStatehouseFile.com, a news website powered by Franklin College journalism students.