Indiana Supreme Court Law Library links past to present with rare book collection

- By Marilyn Odendahl, The Indiana Citizen

- Â

Perhaps Indiana Justice Samuel Barnes Gookins, who served from 1854 to 1857, loved reading outdoors or, maybe, a relative wanted to preserve a special memory. Whatever the reason, a clover was pressed between the pages of his palm-sized Bible which dates from the 1800s.

The Bible, with the clover still inside but now tucked in an acid-free sleeve, is part of an eclectic collection of rare books in the Indiana Supreme Court Law Library in the Statehouse. Although the journey those tomes took to end up on the shelves of the library may remain a mystery, they are a valuable connection to the lessons of the past in this time of video chats and instant messaging.

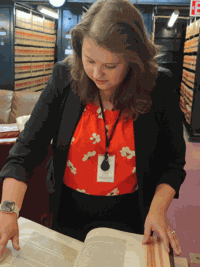

“There’re so many things we can learn,†Cathrin Verano, Indiana Supreme Court Law Library special collection development librarian, said. “Not only the content, but what I’m personally interested in is the ownership history and how people have used these books over time.â€

With the help of a $4,500 grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities, the law library is taking steps to ensure the old and rare books are preserved.

The Preservation Assistance Grant has been used to hire a rare-book conservator who evaluated the books in the collection for about three days in mid-October. She produced a “very detailed, item-level description†of the collection, Verano said, and made recommendations for the repair and care of the books.

Also, the grant will cover some of the costs for archival materials including those used to make the clamshells – boxes that will encase some of the especially fragile books. Verano is putting together an order for the archival supplies such as folders and boxes and plans to work with the conservator to find ways to maximize the remaining grant funds.

The rare book collection of 230 volumes is “just scratching the surface,†Verano said. The law library also has papers from former Indiana justices and records from the now-closed Marion County Law Library.

Key to the conservation project will be making sure the books and papers are accessible to the public.

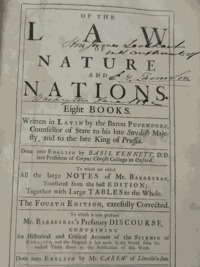

Samuel von Pufendor’s “Of the Law of Nature and Nations†was a book that influenced Thomas Jefferson.  Photo by Marilyn Odendahl, TheStatehouseFile.com.

Underscoring the importance of allowing library patrons to handle the books, Verano pulled a large, heavy, thickly bound copy of Samuel von Pufendorf’s “Of the Law of Nature and Nations,†published in London in 1729. Thomas Jefferson had two copies of this book, one in English, the other in French, and was influenced by its ideas and insights.

“Being able to touch and look at it makes much more of an impact than if you read somewhere that Thomas Jefferson had “Of Law of Nature and Nations†in his library,†Verano said.

‘Context is the key’

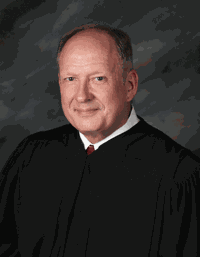

When Judge Paul Mathias of the Court of Appeals of Indiana enters the law library followed by a trail of students, he will pull the firsthand account of the beheading of Marie Antoinette during the French Revolution.

He shows them the text, printed in 1794, and points out how some of the letters look different from modern-day script. Then he has some of the students read the words aloud, lending assistance as initially, they stumble over the stilted phrasing, but soon the story emerges.

The students are transported to the streets of Paris that were lit by torches as Marie Antoinette was taken to the scaffold on an ordinary cart. They learn she bounded up the steps to face her executioner and after the guillotine fell, her severed head was held aloft on all four corners of the platform. A loyalist then dipped his handkerchief in the queen’s blood.

Mathias uses the books to emphasize that “context is the key to almost anything in history.â€

He will open a book with the laws of the Indiana Territory and turn to the section on children and servants. Then he starts a conversation with the students about how children were valued in previous times.

A copy of Indiana statutes from the 1850s is written in German, likely a nod to the flow of German immigrants into the Hoosier state. Mathias will ask the students if a book with today’s state statutes should be printed in Spanish.

“I’ve watched it happen over and over again, that in order to fully understand what was going on at the time, the explanation and discussion about what was going on at the time is pretty sterile,†Mathias said. “It becomes real when a student is holding a book and turning pages, actually reading from sections from the books that we provide.â€

Mathias discovered the rare books in the Supreme Court’s law library about 20 years ago. His favorite is a book of Philadelphia laws that was printed in Benjamin Franklin’s shop.

Other treasures in the rare book collection include:

- A six-penny pamphlet about an actual trial in England, albeit likely a bit sensationalized to grab the general reader. The illustrations are by Isaac Cruikshank, the lesser-known brother of George Cruikshank, who drew the illustrations for Charles Dickens.

- A two-volume legal abridgment that was an early attempt to standardize early English law into something attorneys could reference, similar to a case reporter. It is written in law French, or what Verano described as “Latinized French,†which was the working language of attorneys until about the 17th

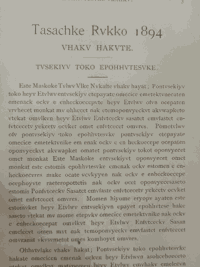

- The 1894 book, “Acts and Resolutions of the Creek National Council,†is described as “parallel printed†because it presents the same text in two different languages. The front half is in English while the back half is in Creek, the language of the Muskogee Creek Indian Tribe.

- A book of verdicts and judgments was published in 1596 by Jane Yetsweirt, one of the first women law printers in England. She gained ownership of the print shop after the death of her husband, Charles, and for a brief period in the 1590s, she held the patent letters that allowed her to print legal texts in Elizabethan England. She printed 13 titles before gender discrimination caught up and the letters were taken from her.

Handwritten notes from the past

Like the clover in Gookin’s Bible, many of the books contain hints of their past. Handwritten names and dates, underlined passages of text and words scrawled in the margins illuminate what a judge, lawyer, or leader from a previous generation was thinking.

Inside the cover of the “Corpus Juris Civilis,†a volume of 6th century Byzantine laws that was published in 1663, is a list of presumably the owners’ names, addresses and the year they each took possession of the book. The dates move chronologically from 1717 to 1875.

“Anytime I see an inscription, I Google that person, and oftentimes it’s been someone who is prominent enough to at least have a Wikipedia page,†Verano said, explaining the first steps she takes when she begins sleuthing into a book’s background. “There’s a lot of research to be done in terms of ownership and, like I say, I hope that will reveal some answer about how some of these items arrived here.â€

Gookins’ Bible was donated to the law library along with a portrait of the justice by a Gookins family member in summer 2021. Actually, Verano said, the book is a common 19th century Bible, but it is valuable in Indiana because it belonged to the 15th justice. He resigned from the bench due to ill health and low pay.

A book about the trial of Katharine Nairn and Patrick Ogilvie is a treasure for more than the printed text describing when the pair was tried in August 1765 in England for the crimes of incest and murder. In the Supreme Court library’s copy, someone at some point had sewn extra pages into the back of the book and then made a “painstakingly handwritten†addendum, copying from another source the rest of the story including Nairn’s escape to America after the trial.

Verano, an art history major who completed her undergraduate degree at Indiana University Bloomington and did graduate studies in England, is aware of the weight of history that accompanies rare books. At one time, tales of 18th century trials might have been gobbled up by the public, and legal reference books published in the 16th century probably had a place on many lawyers’ desks. Their material dated, they now spend more time on a shelf but, Verano said, the books still have value from a historical and scholarly perspective.

“People are interested in them. They get people in the door,†Verano said. “It’s just something that we’re really proud of. We don’t know the ins and outs of how they got to be here, but we’ve been entrusted with these things. It’s kind of our responsibility to steward them properly.â€

This article was published by TheStatehouseFile.com through a partnership with The Indiana Citizen, a nonpartisan, nonprofit platform dedicated to increasing the number of informed, engaged Hoosier citizens.

FOOTNOTE: Indiana Citizen Editor Marilyn Odendahl has spent her journalism career writing for newspapers and magazines in Indiana and Kentucky. She has focused her reporting on business, the law, and poverty issues.