Evansville, a Home for Business

by SCOTT MASSEY-EvansvilleÂ

After graduating from Purdue University in May 2017, I continued to rent co-work space on campus in West Lafayette working for Heliponix full-time until my apartment lease ended at August 2017. At the time, I was hyper focused on the engineering design tasks at hand for Heliponix to debut a new prototype GroPod™ at the Forbes AgTech Summit. After the summit ended, I brought all of my possessions back to Evansville. It occurred to me I was once again living in Evansville only after I had moved back home. Upon moving back, I was asked to speak at Evansville’s Tech on Tap weekly entrepreneurial meetup where I was asked why I came back. I answered, “Evansville is home, and I can continue working on my company without paying myself by living with my parents.†This seemingly obvious answer spurred a new found sense of urgency that if I were to scale a technology company, than I must leave southern Indiana for greener pastures. I then began to look for every possible reason why I should move away from Evansville for the benefit of Heliponix. I identified the following four reasons why I could not headquarter Heliponix in Evansville, Indiana.

- Early adopter customers for new technologies do not live in the midwest.

- Tech companies need investors. Evansville did not have venture funds.

- Tech companies need top tier software engineering talent. Evansville did not have individuals with this skill set on hand.

- Hardware companies such as Heliponix need to manufacture overseas to be cost competitive in the marketplace.

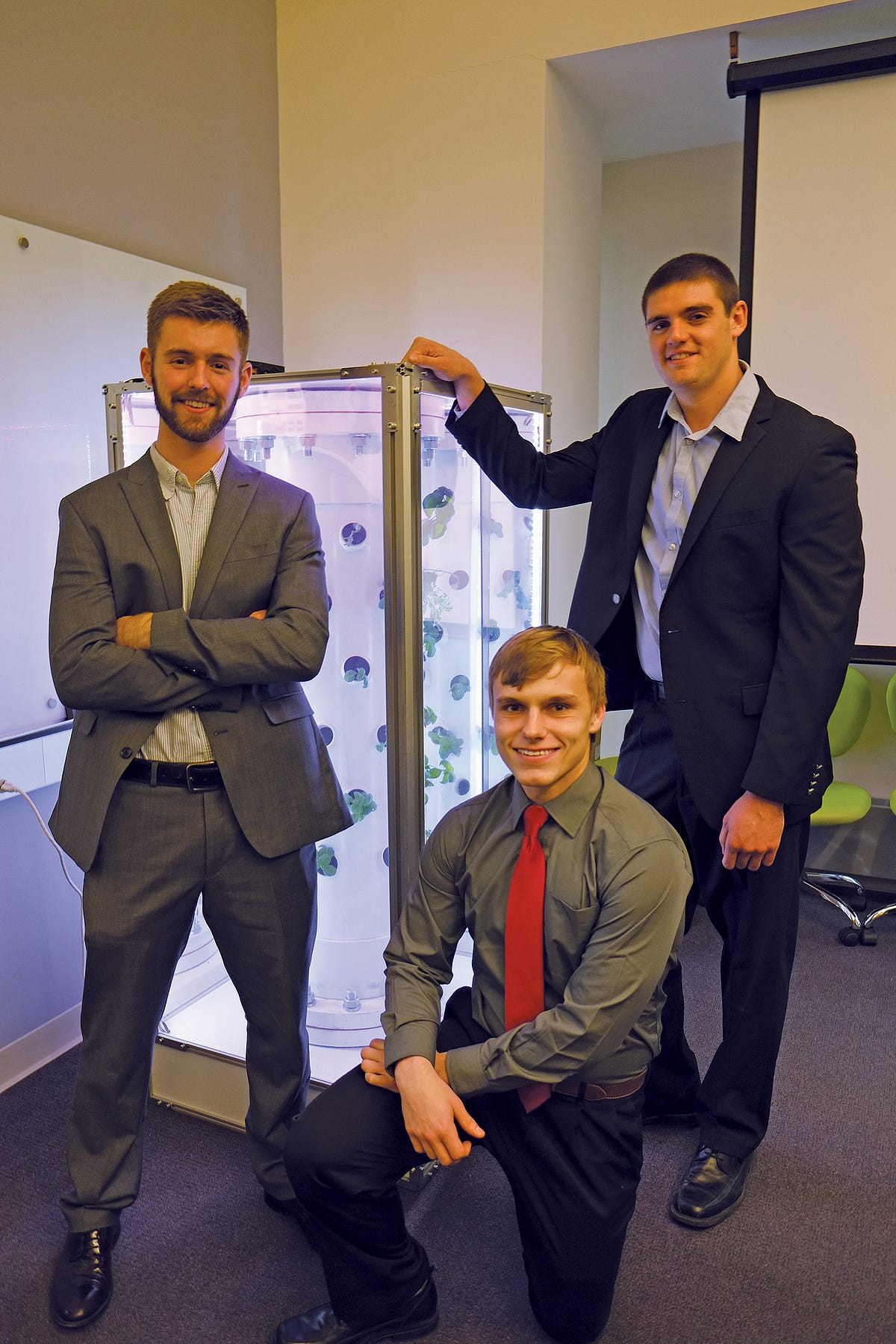

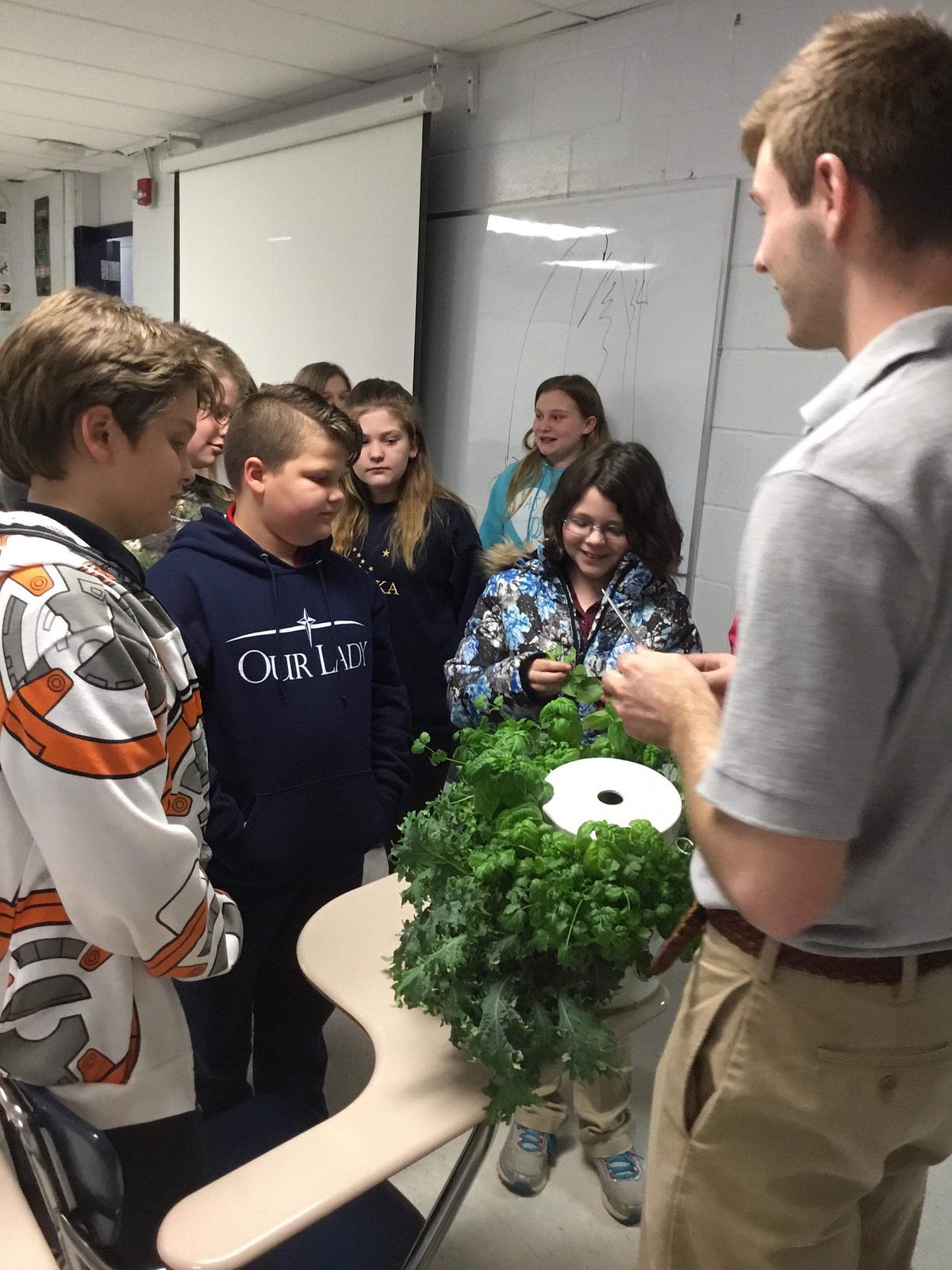

Starting a company without experience or the money needed is comparable to charging into a battle unarmed and unaware of the terrain with dangers ahead. I was acutely aware of my limitations, and spent my senior year at Purdue University delivering newspapers at night for about $9/hour, and competing in business plan competitions between classes for cash awards. Although we were very lucky to have successfully secured over $80k over the course my senior year and a little under $100k from competitions post graduation, the money was the second most valuable aspect of winning these pitch competitions. For every competition we won, at least two or three articles from local media publications would cover the story with our name on the front title. We jumped at every opportunity to showcase our prototypes at schools, STEM career fairs, and also leveraged my position as the lowly delivery boy to publish articles in the Exponent to grasp as much publicity as possible for an early stage company.

For every article and interview that was published, I received an email from random Indiana residents interested in purchasing a GroPod when it became available for purchase. I kept a running list of these potential customers, and reached out to collect a $500 pre-order deposit when we had finally landed on a GroPod design that worked reliably. We had definitively proven that a pre-revenue startup company could launch an expensive product in Indiana if they are able to achieve enough publicity to convert impressions into executed sales. Although there are many more wealthy individuals in major cities who could buy an early stage product; we did not yet have the production capabilities to meet this demand, and still had product development to refine before we would be ready for a massive user base.

Although we had been veryfortunate to secure some funding from business plan competitions for patents and prototype development, we had reached the ceiling of competition funding available in Indiana for an idea not yet generating revenue. My Co-Founder, Ivan Ball accepted a full-time, electrical controls engineering job offer upon graduation to pay off student loans at GPC (Grain Processing Corporation, an ethanol and grain alcohol processing plant in Washington, Indiana) after interning and co-oping as a student for several years prior. Together we worked exhausting hours for a full year to refine the GroPod design until we created a functional product able to generate revenue in Ivan’s garage.

This marked a major turning point for the company after three generations of failed prototypes. When asked if we both worked on Heliponix full-time to this point, I would honestly say yes. Our individual hours spanned 50–70 hours weekly even though Ivan had a full-time day job that took 40–45 hours per week. At this time, we had spent almost all competition award winnings on patents, prototyping, travel for events, or other business expenses. We simply did not have the capital needed to cover materials to assemble the first GroPod betas. I then approached Eric Steele, my Entrepreneur in Residence with Elevate Ventures (Indiana’s state venture fund) seeking capital needed to fund inventory. Eric referred us to the ISBDC (Indiana Small Business Development Center) who advised the Vectren FoundationGrow Local loan program for small businesses. After working with Douglas Claybourn and Kim Howard, we sent an application to the Vectren Foundation board to build the first GroPods. After waiting patiently, we were approved for a loan needed to build these GroPods with very favorable terms for any company, let alone a startup with zero cash flow history. We used the loan to buy all the parts needed, and collected the remaining $1,500 left on each GroPod order with early adopters to sell out of the beta models assembled by hand. We 3D-printed all parts, wrote our own code, soldered our boards, assembled every aspect of the product Ivan and I had designed entirely by ourselves, and delivered each GroPod in person to the early adopters. There was so many GroPod parts laying around Ivan’s home, I had to deflate my air mattress to make more room, and slept on his couch for months.

At this point Ivan quit his job at GPC, to work solely at Heliponix, and sold his house in Washington, Indiana to be fully committed to the company. Today, I am pleased to announce that the risk the Vectren Foundation took on us for funding the loan is being paid back in full plus interest. This market validation thrusted us into the long sought after post-revenue status, which did not go unnoticed by local and regional angel investors; however, this is a story for another day. Despite the undeniable fact that the largest investment funds are in major cities, very few early stage hardware companies receive those investments due to the amount of competitors who rarely manufacture products within these cities, let alone the state. It is much better to refine the product and user experience until a sizable MRR (monthly recurring revenue) is established before approaching these funds which are beginning to invest outside of their states to leverage the capital efficiency of a midwest startup.

Talent

Delivering the first GroPods was just the beginning of a long troubleshooting learning curve with paying customers… Internet connectivity with a connected, IoT (Internet of Things) device will come with many software bugs as well as faulty sensor failures when buying in low quantities from Chinese suppliers. The problems that you are both unaware of, and unable to solve are the hardest any startup will encounter. It is incredibly important to find these problems by getting your product in the hands of early adopters as soon as possible to identify and solve. The dilemma of an underfunded hardware startup company is that you will more than likely need to sell a product that doesn’t yet have all the features needed to make it “perfect†in order to stay cash flow positive. The reality is that no garage startup will be fully ready, and you will certainly find excuses to not be ready if you look for them. This is called the MVP (minimum viable product). Then something amazing happened, customers began to complain less each day as we solved problems one after another, until I began to hear feedback that their GroPods were growing more food than they could consume! This major milestone was met with interest from angel investors who provided the capital needed to hire a full-time software development lead. Unfortunately, there is not a plethora of software developers in Evansville at this time, so we needed to look for a remote employee. After interviewing several developers, Ivan and I decided to hire Bryan Lemon, a PhD computer scientist from West Virginia University living in South Carolina. Bryan’s experience with IoT device companies translated very well into solving problems, creating new features that kept customers happy, and attributed to our zero-percent churn rate. Despite never meeting Bryan in person, we were quickly able to determine his technical ability by first hiring him as an independent contractor for an agreed upon milestone. I strongly encourage that early stage technology companies consider remote software developers to save cost, expand your professional network, and reach a wider pool of candidates to only hire top talent. You do not need to go to the bay area or other major cities to find top talent, and the operational cost of your business will increase by multiples if you move to a larger city.

Manufacturing

I remember all too well the day that the Whirlpool plant in Evansville shut down for the last time, a major manufacturing hub for appliances that employed several thousand people. At a very young age, this instilled the idea that hardware manufacturing companies must leave the United States in order to find competitive manufacturing prices. That is why I took a flight to Shenzhen, China to tour contract manufacturing plants. This massive manufacturing city is often called the hardware capital of the world based upon its speed, competitive labor, and material rates. After returning and considering the cost of manufacturing overseas, I began to factor in the not-so-obvious costs of building products outside of Evansville. The language barriers requires a translator to be present, and often leads to misunderstandings that can be very costly mistakes. The logistical challenges, uncertain trade relationship, and intellectual property theft quickly amounted to a cost that far exceeded that of domestic contract manufacturers. Most startup companies fail by aimlessly pursuing random goals without strategy as capital dwindles. I have discovered that the resources I need to prototype and manufacture are widely available within the Midwest ecosystem. We then began to look locally for contract manufacturers within the Evansville-Cincinnati-Louisville trifecta that had worked at GE and Whirlpool appliance manufacturing plants and engineering design centers. Without disclosing trade secrets, we can confirm that the midwest has manufacturing capabilities that are very competitive with international rates. In our case, we were able to source almost all parts needed in manufacturing from Indiana, Illinois, and Kentucky. In addition to Evansville and Louisville being the former appliance manufacturing capitals of the world; we have been able to find top tier talent and industry partners with relative ease. Eventually, most hardware companies manufacture overseas when they exceed 1,000–10,000 units per year, but automation is the equalizer in a world where labor can be bought for a few dollars per hour, or be subsidized by a country in the process of industrialization. Indiana is uniquely positioned to be an entrepreneurial hotbed with several investment groups, and countless angel investors in one of the top manufacturing states in total manufacturing GDP (Gross Domestic Product).

Conclusion

After speaking to countless successful and not-so-successful entrepreneurs; I believe that starting a company requires two things.

- The drive to achieve your goals

- The means to achieve your goals

This has led to a new revelation about Evansville; it is not a good place to start a company… it’s a great place to start a company. It is uniquely large enough to have the means to fund a startup company, but not so large that the means become unobtainable to newer companies. The cost of living combined with these resources will triple to quintuple how far your dollar will go as opposed to a startup in a major city.

I now proudly say that Heliponix is based in Evansville, and we intend to stay here for the foreseeable future. We will continue to directly and indirectly create new jobs as operations expand. This only leaves one question from me to you, “Why not stay in Evansville?â€.