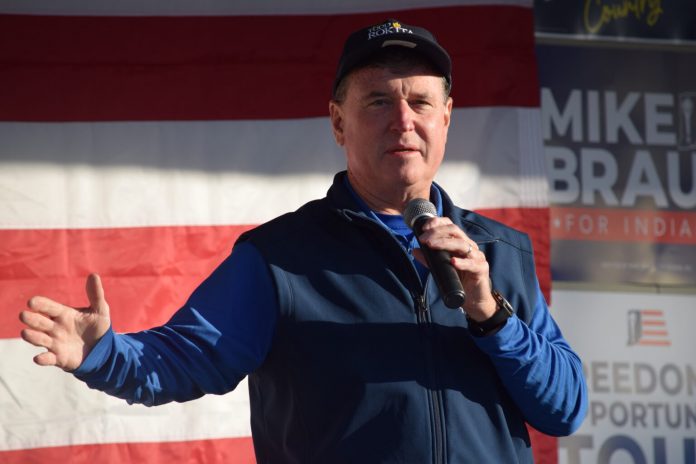

The three-person panel overseeing the case also rejected Rokita’s Ant-SLAPP defense.

BY: CASEY SMITH, Indiana Capital Chronicle

The panel overseeing Indiana Attorney General Todd Rokita’s professional misconduct case denied his effort to force the state’s disciplinary commission to turn over internal records and instead set the matter for a December hearing.

In two orders issued Friday, the three-member panel — Indiana Court of Appeals Judges Cale J. Bradford and Nancy H. Vaidik, along with former U.S. Magistrate Judge William G. Hussmann Jr. — said the only question before them is whether Rokita “violated his duty of candor to the Supreme Court by admitting that he had violated the disciplinary rules without really meaning it.”

Rokita’s defense lawyers sought to obtain internal communications from the Indiana Supreme Court Disciplinary Commission about him and the motives for its investigations.

They argued his comments were protected by the First Amendment and claimed the commission’s complaint violated Indiana’s Anti-SLAPP statute, which prohibits frivolous lawsuits aimed at silencing critics.

We cannot see how any internal communication, investigation, or other information gathered by the Commission could shed any light on Respondent’s state of mind when he indicated to the Supreme Court that he had taken responsibility.

– court order issued Friday, Aug. 22, 2025

Earlier this month, Rokita formally replied to the commission’s allegations, denying that his 2023 press release contradicted his sworn statements to the Supreme Court. His defense maintained the case was an attempt to punish him for protected political speech.

But the panel flatly rejected those arguments.

The judges ruled that such internal records fall outside the scope of the Indiana Supreme Court’s guidance, which limited the case to whether Rokita “intentionally misled” the justices in 2023, “thereby violating his duty of candor, and nothing more.”

“Because the matters for which Respondent [Rokita] seeks discovery are not before the Panel, they are not relevant, and we therefore deny Respondent’s motion to compel discovery in all respects,” the panel wrote.

Panel rejects Anti-SLAPP defense

In Friday’s discovery order, the panel said Rokita cannot pursue an Anti-SLAPP defense because disciplinary proceedings are “neither criminal nor civil” and no U.S. jurisdiction has allowed such a defense.

The panel cited precedent from Rhode Island and emphasized that “the purpose and application of the anti-SLAPP statute are wholly inapplicable to attorney disciplinary proceedings.”

“The respondent is not being sued for his exercise of First Amendment rights of free speech; rather, he is the subject of a disciplinary complaint, deriving from his conduct as a licensed attorney … ,” the panel wrote. “We find no merit in respondent’s claim that this process is somehow being used as a vehicle for chilling his free speech rights.”

The panel denied the discovery requests entirely, noting they were all aimed at supporting Rokita’s argument that the case was meant to chill his free speech.

“We cannot see how any internal communication, investigation, or other information gathered by the Commission could shed any light on Respondent’s state of mind when he indicated to the Supreme Court that he had taken responsibility,” the order continued.

The panel further ruled that no motions to delay or dismiss the case will be entertained going forward and ordered all discovery to be completed by Nov. 12.

A separate scheduling order set a full evidentiary hearing on the case for Dec. 18 in Marion Superior Court, to continue “until completion.”

Preliminary witness and exhibit lists are due Sept. 18, followed by a pre-hearing on Sept. 30 and a final pre-hearing on Nov. 19. Final witness lists and pre-hearing briefs must be filed by Dec. 4.

The panel also urged the parties to attempt mediation within 45 days, naming three potential mediators — former Indiana Supreme Court Justice Steven David, and Indianapolis attorneys Patricia Polis McCrory and James Riley Jr. The parties must report back to the court if they’re able to agree on one.

The three-judge panel will oversee the trial-like hearing and make a recommendation, but the Indiana Supreme Court will ultimately decide whether Rokita faces discipline. That discipline could range from another reprimand to law license suspension or disbarment.

An ongoing saga

The disciplinary commission’s case stems from Rokita’s public comments in 2022 about Indianapolis OB-GYN Dr. Caitlin Bernard, who provided abortion care to a 10-year-old rape victim from Ohio.

The commission alleged that Rokita’s Fox News interview remarks risked prejudicing proceedings against Bernard and served “no substantial purpose” beyond embarrassing or burdening her — violating Indiana’s professional conduct rules for attorneys.

Rokita’s office settled an initial complaint about his comments in November 2023. In a sworn affidavit, Rokita admitted to violating two professional conduct rules in exchange for a public reprimand. A third count was dismissed.

The Indiana Supreme Court approved the agreement, publicly reprimanding the Republican attorney general. Bernard was also disciplined before the Medical Licensing Board for discussing the procedure publicly.

Although he agreed not to contest the charges, the conflict resumed after Rokita issued a news release and gave interviews suggesting he had not actually done anything wrong. He said he had “evidence and explanation” for what he said on air, but chose not to fight the complaint any further to save “taxpayer money and distraction.”

The commission filed a new complaint in January, accusing Rokita of misleading the court and misrepresenting his acceptance of responsibility in the earlier disciplinary case.

The commission said Rokita acted with “a deliberate or reckless disregard for the truth” and has since opposed his request to dismiss the new charges.

Rokita attempted to get the new complaint dismissed, but the state supreme court ruled in July to let it go forward.

The attorney general has consistently maintained the professional conduct proceedings are the result of a politically charged and unaccountable disciplinary process.

Public records show taxpayers have already spent nearly $500,000 on Rokita’s legal defense in the matter.

Rokita flatly denied each allegation in his latest response and claimed the commission created “widespread confusion in the media” by pursuing charges it had already agreed to dismiss.

His lawyers also cast the complaints against him as partisan attacks, maintaining that, “Democrat activists filed complaints against him for politically motivated reasons” and insisted that Rokita “denies ethical misconduct or that he was dishonest with the Court.”