Erin Gibson

USI Instructor in Journalism

Student Publications Manager/Advisor

Editor’s Note: Erin Gibson is available to speak to media on issues related to media literacy, fact-checking and how people are sharing news and information through social media. To set up an interview, please contact Ben Luttrull, Media Relations Specialist, at bluttrull@usi.edu or 812-319-7673.

View this release in a browser

How many of these claims have you seen in recent weeks?

- Ibuprofen is not safe if you have COVID-19. (False.)

- Inhaling hot air from a hair dryer will kill the coronavirus. (Dangerously false.)

- 5G mobile phone technology is spreading the coronavirus. (An absurd conspiracy-theory. Also, just stop it.)

Misinformation and disinformation are spreading at an alarming rate during the COVID-19 pandemic. Just take a look at this running list of coronavirus hoaxes compiled by BuzzFeed News, and you will see we clearly have a problem.

False information has become so pervasive that the World Health Organization director-general called the situation an “infodemic.â€

“Fake news spreads faster and more easily than this virus, and is just as dangerous,†Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus told the Munich Security Conference in February.

Just as we rely on medical experts to provide guidelines to stop the spread of the COVID-19, we must also rely on information experts to tell us how to stop the spread of misinformation.

Here are some steps to help you evaluate what is true and what is not.

PHASE 1: Whoa! Wait. What?

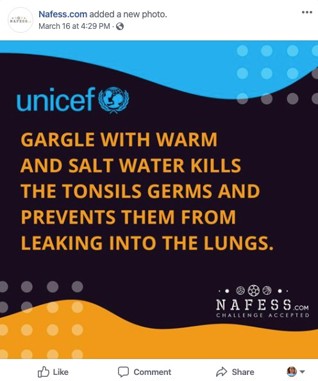

Be skeptical about news and information and recognize that your emotional responses can mislead you. For example, when you see a post like this on Facebook, your first reaction, might be, “I didn’t know that.â€

I call this the “Whoa!†response. It’s a natural reaction to learning new information.

But don’t act on the information until you do some digging. In other words: “Wait.†Before you share information, take a moment to consider: is it true?

That leads to the “What?†part of the process, which is a series of fact-checking steps (see Phase 2) to help you tell the difference between good and bad information.

A key point in the “Whoa! Wait. What?†process: if you don’t have time to check it, you don’t have time to share it.

PHASE 2: Verify information

A good place to start the verification process is to ask yourself, “Is this information trying to inform me, entertain me, persuade me or mislead me?â€

Anyone who publishes information has a motive. If you can identify it, you have a better idea whether the information you have encountered can be trusted or not.

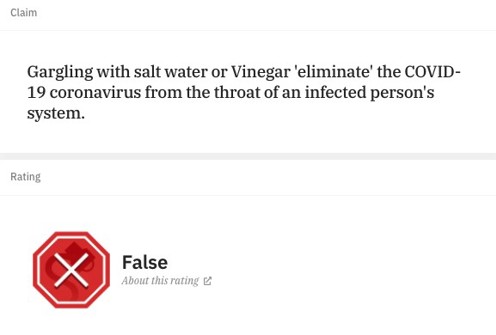

Next, check if the information has already been verified or debunked. Use Snopes, Factcheck.org or Politifact to search for key words to see if trusted fact-checkers have already done the work for you.

We just read a claim that gargling with salt water will kill COVID-19 germs. When we visit Snopes and type in “gargle COVID-19†we learn that Snopes has flagged it as false information.

If fact checking websites don’t work out, the last two steps of the verification process require you to evaluate the source of the information and the claim it is making.

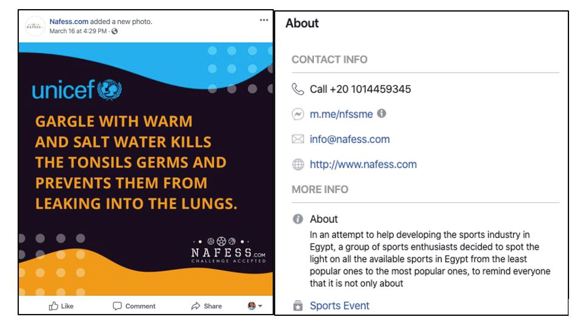

What does the source say about themselves? Visit the About section of the website or social media page where you found the information. (This is called vertical reading.)

Let’s return to our example: the gargling with salt water claim came from a post on a Facebook page called Nafess.com. When you go to the page’s About information, you see that the description is poorly written and incomplete. It also claims it is a page for the sports industry. This page is clearly not a reliable source of health information.

But what about the claim itself? It appears to be advice from UNICEF. Is it?

If you use Google to search “gargle and UNICEF,†the results reveal a series of articles from reliable news sources that reveal this information was fabricated.

You could also search for Nafess to see if any reliable news organizations have ever written about them (they haven’t).

This step, called lateral reading, requires you to look beyond the original information and to check with other sources, such as trustworthy news organizations, to see what they say.

Seek out reliable information

The need to evaluate information is often related to another issue. Many people use their social media feeds as their primary source of information.

That practice limits the amount of reliable information and variety of viewpoints you encounter each day.

Break out of your information bubble and develop a daily habit of seeking out information in addition to the information that finds you.

So, where do you start? Trusted news sources.

- Subscribe to your local newspaper’s website. (Yes, that means paying for your news).

- Download the Associated Press app and start each day with “10 Things to Know Today.â€

- Catch a top-of-the hour NPR newscast on your local public radio station or listen to the latest one anytime online (click Listen Live).

- Watch the first 15 minutes of a nightly network (ABC/CBS/NBC) nightly newscast.

- Subscribe to the New York Times and/or Washington Post (Again, for emphasis, pay for your news.)

Finally, I recommend following news and media literacy organizations that are using social media in fun and informative ways to teach fact checking skills. Here are some of my favorites:

- Media Wise (Instagram, TikTok, Twitter)

- The News Literacy Project (Instagram, Twitter)

- Not So Fast Campaign (Instagram, Twitter)

We’re in this together

Anyone with an internet connection can access and publish information – and misinformation –from anywhere and at any time. That means we have an enormous amount of information to wade through to separate fact from fiction. It’s an effort that (much like the fight to contain COVID-19) requires all of us to do our part.

And some in those recommended sources pushed the Russia collusion hoax.

Speaking of fake news, USI had a journalist student at the Trump rally back in 2016, the student claimed someone spat on her, never happen, but was not investigated and taken as truth. Another instance of fake news was the chipped window at the Jewish temple off Covert and 69. It was listed as a hate crime by our mayor and the rabbi. The fbi said the window was chipped by a low powered projectile, meaning a rock or something similar, this building is located adjacent to a play ground, 2 major roads and an area that gets mowed. The fbi said it was Probably a Hate Crime, as if the fbi has any credibility left. It appears that the Juicy Smollett syndrome is alive and well in Southern Indiana. Even our nominal republican mayor weighed in on it as a hate crime with no factual evidence.

Comments are closed.